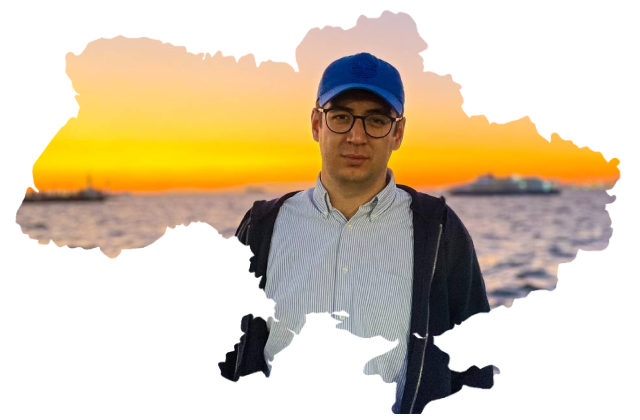

Artem Savchenko

Businessman, social entrepreneur, cultural event manager, psychotherapist

Kharkiv — Yablunytsya — Ivano-Frankivsk — Lviv — Kyiv

I love Kharkiv and had no intention to move anywhere. Back in the day, I spent five years in Kyiv, where I had a lucrative job and an apartment of my own. But at some point, I realized that I loved my native city too much, so I returned.

I didn't prepare for the war, apart from the fact that the fuel tank in the car was full. I didn't believe it would happen. I thought that there could be an escalation in the regions that were already at war, but I'd never imagined that war would come to Kharkiv.

My friends and I were planning a big festival and negotiating with partners right before it all started. In addition to that in August 2021, I signed an agreement with the developer on purchasing an apartment, which was supposed to be ready in a year. I paid half of the price and continued to pay the rest each month. I kept on doing that even in the first few months of the war until it became clear that I would see neither a new house nor a refund.

On February 23, I had a therapy group session where we talked about the fear of war, and we agreed that we should think positively and believe that nothing bad would happen. But I remember well how on returning home after the session it struck me that there were no parked cars outside, even though there were usually plenty of them parked near the building.

My girlfriend, Anya, and I had plane tickets for February 24 from Kyiv to Copenhagen at 7 pm. Thus, on the 23rd we packed two small suitcases for a three-day trip and went to bed. At five in the morning, we woke up to explosions. I checked the news channels and saw a big headline that read, "War!" I couldn't believe it. It was a real shock.

My girlfriend's mom served in the ATO, so she was well versed in military affairs. She warned us about a possible threat, constantly reminding us to keep the tank full and, in case of danger, to go to her place in western Ukraine, where she had recently moved.

We left as early as six in the morning. We only took the things we packed for the Copenhagen trip. We were still hoping for the best, so we thought we were leaving Kharkiv for a week or two.

Our first stop was in Kyiv, where we had to pick up some of our relatives' stuff. As we got out of the entrance, we saw fighter jets circling over the building. Kyiv was being bombed at that time; there were air battles. Everywhere was so loud. We doubted what to do next: leave the city or run to the basement. We simply froze. Suddenly, there was that old man walking by and exclaiming: "Guys, you've gotta get out of here!" We thought of that as a sign quickly got in the car and drove away.

There was a lot of traffic everywhere. I remember standing for more than six hours at the bridge behind Bila Tserkva. A few hours after we crossed it, the Ukrainian armed forces blew it up to detain the Russians.

It was already my second day of driving without any sleep. I started hallucinating about rockets, so we decided to stop for at least 30 minutes or an hour to get some rest. It was in the morning, at about 4 a.m., 150 kilometers away from Ivano-Frankivsk. There were cars parked everywhere along the road: drivers stopped to get some sleep at every spot that looked more or less safe. We stopped right on the highway, behind a truck. Although it was cold and uncomfortable, I zoned out in a second. Then I woke up just as quickly, terrified that someone might steal our fuel canister while we were asleep.

As we drove on, it hit me hard: I realized that I didn't want war, I didn't want any of that at all. That was a real panic attack. I rushed to the bathroom of the nearest filling station to rinse my face and come to my senses.

At seven in the morning, we arrived in Ivano-Frankivsk at an apartment in a khrushchevka building that Anya's mother had found for us for a few days. It was a great relief. For we felt like hunted prey, terrified of humans. We needed a shelter to hide away and take some rest, and someone kind to give us safe space. In those days, Anya's mother would often say with tears in her eyes, "Thank you so much for bringing my daughter." Those were emotions that we will probably never experience again.

However, we had a feeling that we needed to move on, away from the city. We wanted to head to the mountains and there, in safety, decide what to do with this new life while the country was torn apart by war. So we drove to Yablunytsya, outside Bukovel, to a hostel that sheltered us. I started calling all my friends, saying, "There are rooms available here, please come. If you need shelter, need money, or anything else, I'll help." That's when I realized especially clearly that my strength was in those around me.

I'm the type of person who can't sit still for long. On the third day after the full-scale invasion began, I was already looking for an opportunity to provide humanitarian aid. Thanks to my clients I had logisticians and warehouses all over Ukraine. I had acquaintances among the Kharkiv officials to get permits for drivers to travel.

I helped with the transportation and storage of humanitarian aid to all the volunteer hubs I know. Culture Shock, the volunteer headquarters established by Kharkiv musician Oleh Kadanov, and the Rescue Now charitable organization founded by actor Ihor Klyuchnyk were among them. Some had full busloads of aid, while others loaded up half of a vehicle, so I stationed all the aid in my warehouses all over Ukraine. Then we loaded up cars and hired drivers to take them all the way to Kharkiv or found people who would do that for free. Our warehouse in Kharkiv would have everything sorted and distributed to different volunteer centers. I just had to do something. That was my way of controlling the situation and it gave me the perspective that things weren't so bad.

We stayed in Yablunytsya for a month. Then we went back to Ivano-Frankivsk into an apartment that was very similar to the one we lived in Kharkiv. It gave us a sense of home and reminded us of the life we'd had. So we stayed there for a month before we moved to Lviv in early May for a few weeks. We had many friends staying there. Later, when Russian troops left the Kyiv Oblast, we decided Kyiv was the place we wanted to be. We moved to the capital and visited Kharkiv to say goodbye to our past life.

After the first week of the war, all the windows in our Kharkiv apartment were blown out, and the apartment stayed like that for two months. When we came in, we saw houseplants scattered all over the place. The whole building was shattered by the blast wave; it looked devastating. So we moved our stuff out and left for good, knowing we weren't coming back anytime soon.

Now we aren't making big plans. I realized that I can't do long-term projects. Now I work with "shorter distances". Looks like a kind of crisis management: I plan for two weeks, and then again for another two.

The war has made me realize that I'm going to be fine no matter what now that I've got the experience of doing anything, anywhere. I've gained this confidence namely from working in the humanitarian movement with people of different professions and with different expertise. In addition, I began studying to be a project manager, so I have a profession in IT, and this experience is also good for business. This way, I'm building a new support system for myself.

Recorded by Alyona Vorobiova

Translated by Volha Mikhnovich

Photographed by Ekaterina Pereverzeva