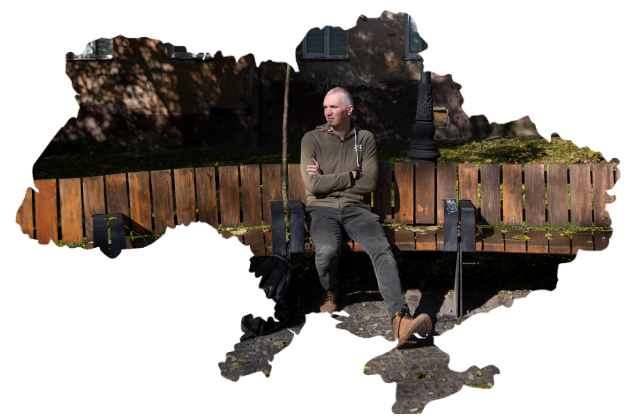

Oleksandr Manukians

Designer, architect

Donetsk — Mariupol — Kyiv — Bucha — Kyiv

In the spring of 2014, when I guess not everyone in Donetsk realized that the situation was bad, I felt a clear urge to get out of there.

I participated in the Euromaidan in Donetsk, and it was inspiring because I saw that I was not alone. But as soon as the first person died, I decided I wouldn't go there again. For me, my life - both at that time and now - was more important...

Most of my acquaintances were just waiting it out. Everyone had witnessed Maidan and the Crimea, but they would tell me about Donetsk: "Don't worry about it! It will all clear out. It's all for TV.” However, there were certain powerful visual symbols that hinted to us that that wasn't the case.

I was dating a girl from Mariupol at that time, I went to visit her, and noticed checkpoints that started appearing along the road. One day I noticed the anti-tank hedgehogs and thought, “They are set up to keep armoured vehicles away. This means someone assumes that these armoured vehicles will be coming. Shouldn't I be as far away from here as possible?" That was the first trigger.

The second disturbing call came as a real shock. It is an image in my head that cannot be wiped off. I was travelling through the city on a commuter bus. While passing the ring at the Bakyns'kykh Komisariv square, we went in one direction, and from another run, armoured vehicles with Russian flags were moving. And several women in the minibus said something like, "Hurrah! They've come to liberate us!" It was a sign to me that I had to do something, run, get out of there.

I almost immediately decided to move to Mariupol. In Donetsk, I managed to get my bachelor's degree, but the territory of the IZOLYATSIA cultural initiatives platform, where I worked, was seized by the separatists. I dangled it before my parents that I could no longer stay in Donetsk, neither physically nor psychologically. For me, it was a difficult but obvious decision. I was leaving for the unknown.

In Mariupol, I was well received by my ex-girlfriend's family. I tried to find some kind of job right away because it was uncomfortable to sit on their neck. I found some options. The IZOLYATSIA team moved to Kyiv, they invited me.

A few months after the first shelling of Mariupol, we decided to move to Kyiv. At first, I was able to find an apartment relatively easily, but with the next search, I began to encounter prejudice against the people from Donetsk. The apartment owners were afraid that they would be scammed somehow, they told me, "Well, we have heard from acquaintances of acquaintances, we know there are some such cases..."

I haven't changed apartments in Kyiv often, because it's both a hassle and a financial burden, and there is also a psychological barrier because of these unpleasant issues. It surprises, offends and irritates me. You're scrutinised carefully to ensure that you don't seem somehow untrustworthy. If I let go of my beard a bit and didn't get enough sleep, or had a cold - my chances of renting an apartment would be much lower simply because of the formal inscription in my passport.

On the one hand, I'm sad that there are more and more displaced people. But on the other hand, because of this, the state changes its attitude toward us, and our problems are resolved faster. When I began this path of a displaced person, I went strictly by the rules, without corruption and agreements. And every time it was extremely difficult and time-consuming.

Staying focused on work helped me get through difficult times. But because of that, I was forgetting to live, and problems began to arise in every sphere except work. I still feel that I devalue my achievements. For a long time, I was afraid of being out of a job and didn't know how to say no. This stretches back to 2014-2015, when I jumped at everything, even if it wasn't related to my line of work. For any money, just not to stay on the sidelines, to pay the rent, to buy food.

A little over a year ago I opened my own architecture and design studio. For each season I made a mini-plan of projects. I made the last one, for winter-spring 2022, on February 22 or 23. I was ready to head into the new season. But a full-scale invasion happened.

My girlfriend, her friends, and I decided in advance that we would definitely leave town to go to her parents' house. We did not consider that the attack could come from Belarus. So on February 24 we quickly packed our documents and a bare minimum of belongings and quickly set off for Bucha.

Most of the time we all stayed together in the basement. In the beginning, when it was not so scary, I was constantly told, "Well, you have experience, you come from Donetsk, you know how to behave!” But I had no such experience at all, I left Donetsk quite easily.

The scariest thing I saw over the years was on the road from Bucha. When we joined the column of packed cars and passed by people without cars. They were banging on the windows and doors, "Take someone!" And we couldn't do it. It was terrifying to see shelled civilian cars along that road with "Kids" signs on them. And it was scary when armoured vehicles with Russian soldiers approached us. Their weapons were aiming in our direction.

We spent more than two weeks in Bucha. After what we had experienced, we just wanted to be as far away as possible, so we evacuated to the Khmelnytskyi region, but soon returned to Kyiv.

From the first days of the full-scale invasion, my friend and his colleagues launched the "Design for real war" group, and after the evacuation from Bucha, I joined them almost immediately. We helped create a hostel for displaced people in Khust, Transcarpathian region. We equipped public spaces with furniture. And it grew into a full-fledged line of Peremebli.

The state of temporality is constantly with me, I often move from workshop to workshop and try not to get too many things. That's why I was constantly collecting all these solutions and design ideas, learning from other designers. And here the context, the request, the user, and the team came together into a more comprehensible product.

In general, I have the feeling that my Donetsk no longer exists and will never exist. I only went there once to visit my parents. And it was a difficult experience. It was as if time had stood still there: nothing had changed in the central part of the city, there were just fewer people there. The locals were so proud that their place was clean! So clean, in fact, that it gave me the creeps. But this "cleanliness" is unemotional, I felt no life there. I didn't feel at home.

"What is home?" is a question without an answer for me. I don't fully understand if I have one. Little by little I try to solve this mystery, then it gets confusing again. But at that time, in Donetsk, I realized that it was not my home.

I still feel responsible for what happened in early 2014 in Donetsk: that we weren't loud enough, not numerous enough. I'm proud of Kharkiv, and Odesa, that they were able to resist, even Mariupol managed that time. And that's why I believe in ordinary people. I understand the power of politics, and weapons, they often win. But I still believe in individual actions. This belief remained with me since then.

I remember when my friend Danya and I bought yellow and blue duct tape in 2014, we walked around Donetsk, tearing down "DNR" stickers and sticking little flags everywhere. These were such micro gestures, and it was already a little dangerous at the time, but we tried to do the bare minimum to make at least some impact.

If I can make a difference with my professional work, my opinion, my word, and my support, I'll try. It may not work out, but I might get lucky, too.

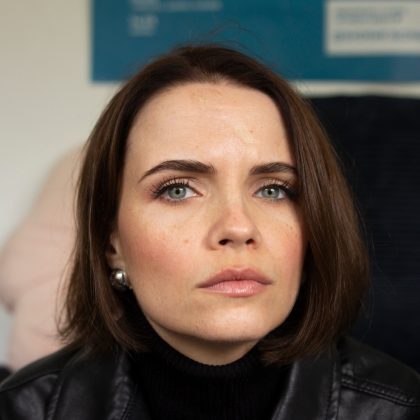

Recorded by Nadiia Mykolaienko

Translated by Katsiaryna Khinevich

Photographed by Ekaterina Pereverzeva