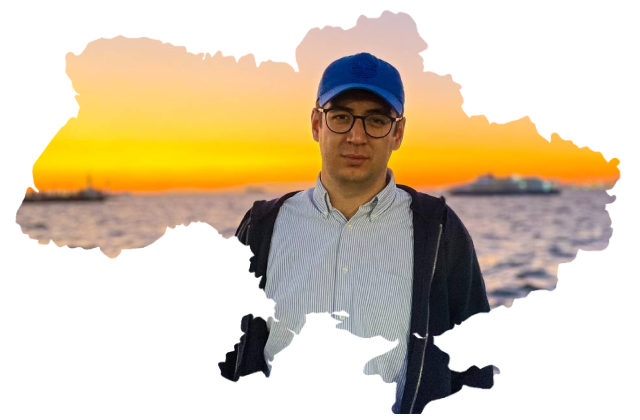

Igor Pavlov

Embryologist, tattoo artist, currently doing military service in a military hospital

Kharkiv — Chernivtsi

Before the war, I worked in a Kharkiv hospital as an embryologist, making kids from test tubes. It was a good job — necessary and cutting-edge. I have a son, he is three and a half years old, so I know very well what happiness parenthood brings.

On February 17, I asked at work, "Are we going to have any meeting about the war?" But I was told, "What war are you talking about?" I said, "What war? We're in a state hospital, everyone here seems to be talking about war, and we've had counter-diversionary exercises at the SBU for the second month in a row. Anything can happen." Because I thought there were wake-up calls and warnings everywhere.

Sometimes I check Flightradar, a web service that shows planes in the sky. A week before the war, I noticed that private planes flew out of parking lots in Kharkiv toward Kyiv and Lviv. I remember vividly the evening of the 23rd. At nine o'clock, after work, I went with my son to Shevchenko Park. The sky was starry, there were no planes, I saw somewhere in the telegram channels that Kharkiv airport was closed for departures and arrivals. And as I walked, I looked at those stars and thought, "Today the weather is so clear for the first time in February. If Putin had decided to launch an attack, he would do it today.”

February 24 was my day off. I planned to go to the dentist and to the military enlistment office to check in because I am a conscript. At five in the morning, my mother called me and said that they were fired at and that the war had started. My parents live near Lyptsi, which is three kilometres from the Russian border — their village was occupied during the first hour of the offensive in Ukraine. My mother called, and five minutes later the explosions in Kharkiv began. And that is probably the scariest call and the scariest nightmare that there could be. When I want to go back to those feelings, I recall that very call every time.

The confusion I felt, and the lack of understanding of what was going on seemed scarier than what I experienced when Kharkiv was shelled.

We lived in the centre of the city, on Rymarska Street, near the Kharkiv Philharmonic Hall, in an old wooden house. Staying at home was a bad idea. An acquaintance of ours, the owner of the Midnight Bar, which was not far from our house, invited us over. The bar was not a bomb shelter, but it seemed safer to be there than at home or in the basement. It was warm and dry there. But I was struck by how diverse the company that ended up there was. On February 24, my son and I came to take shelter, and some people came there for a drink. Those people had only one desire: to get drunk and wait for it all to end.

A week later fighters began bombing the centre of Kharkiv. It was on that day that they bombed our house as well. Hearing those planes was the most horrific thing of all. Sitting in the basement, you could hear that plane turning around above you, heading somewhere else. In those moments everyone would freeze and wait.

I remember going outside after that bombing, and then I felt that the war had begun: an empty city, damaged houses, broken glass, burnt-out cars. You started to understand your fear and it was the fear of war.

I didn't think that they would bomb Kharkiv, because it is an industrial city, and nobody needs it destroyed. But when I saw with my own eyes that my predictions and reality did not match, I clearly realized that the attackers would spare no one. I saw that bombs were dropped randomly, that it was a roulette — you could either get lucky or not. I understood that there would be no clear rules in this war and we had to leave.

Why did we choose Chernivtsi? My wife and I got married there. When we decided to get married, we started looking at registry offices in Kharkiv, and they all looked so miserable and soviet... My then fiancée said she wanted nice pictures and started searching on the Internet for the most beautiful registry offices in Ukraine. And she came across Chernivtsi. We really liked the city then, because it is very people-oriented. The houses everywhere are gorgeous, but not painted, with small cracks in the walls, as if slightly neglected — it's very beautiful but you should be able to notice this beauty.

So we decided to go to Chernivtsi. We stopped in Pisochyn, left our two cats there, drove to Dnipro, spent the night there, and left for Chernivtsi the next day. I had asked my wife if she and our son were ready to endure a marathon of more than 1,000 kilometres, and in 28 hours, non-stop, drove from Dnipro to Chernivtsi.

We used the hotline and ended up in a dormitory. From there they sent me straight to the enlistment office, allowing me to check in only my wife and son. At the commission, they told me that I was fit, so I had to go to the meeting tomorrow. A real panic struck me, but not because they were sending me to war — the most frightening thing was that I had brought my family with me and had to leave them.

I went to the military registration and enlistment office to fill in the documents, and my commander asked me, “ Where did you work?” I answered, "In the hospital in the laboratory.” I showed him all the documents and he said, "You will go to the hospital to work. Tomorrow at 9 a.m. you have to be there.” I asked him, "Can I sleep until ten o'clock because I haven't slept in a day and a half?" He said, "Come at 11 o'clock, take your time.” The next day they called me to the personnel department to sign the oath. That's how my service began.

At that time I had a lot of energy, I wanted to move the walls: I felt that I was important, that I was in my place. I also realized that I could change a lot of things. I came to the laboratory, looked at the equipment, and technically improved it thanks to my friends' financial help, everything started working, and it became easier. Before the war, I worked as an engineer for the maintenance of medical equipment. So in addition to interpreting laboratory tests and working in the lab, I have been repairing this and that at the same time.

It's important to me that I'm useful, that I work for the army. I like to help the soldiers who are being treated in our hospital. I go out into town and buy them cigarettes, or bring them water or coffee if they're on crutches. Or just talk to them because at times there isn’t enough communication. Sometimes it's even more important than what I do in the lab.

As for housing, we stayed in the dormitory intentionally, because when you live there, you retain a sense of being on vacation. That is, that you have not moved here permanently, but only temporarily. After all, I want to go home, I really do.

Recorded by Alyona Vorobiova

Translated by Katsiaryna Khinevich

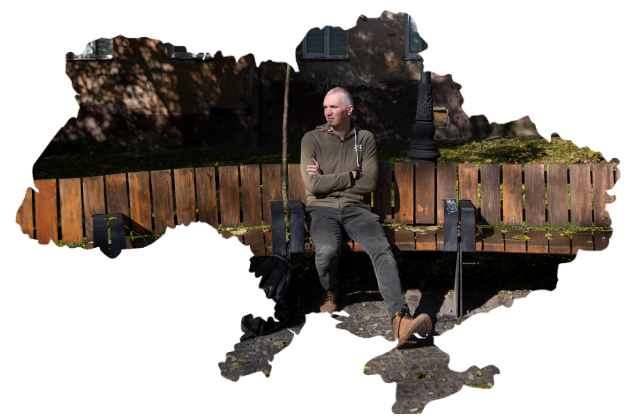

Photographed by Vladislav Yevdokymov