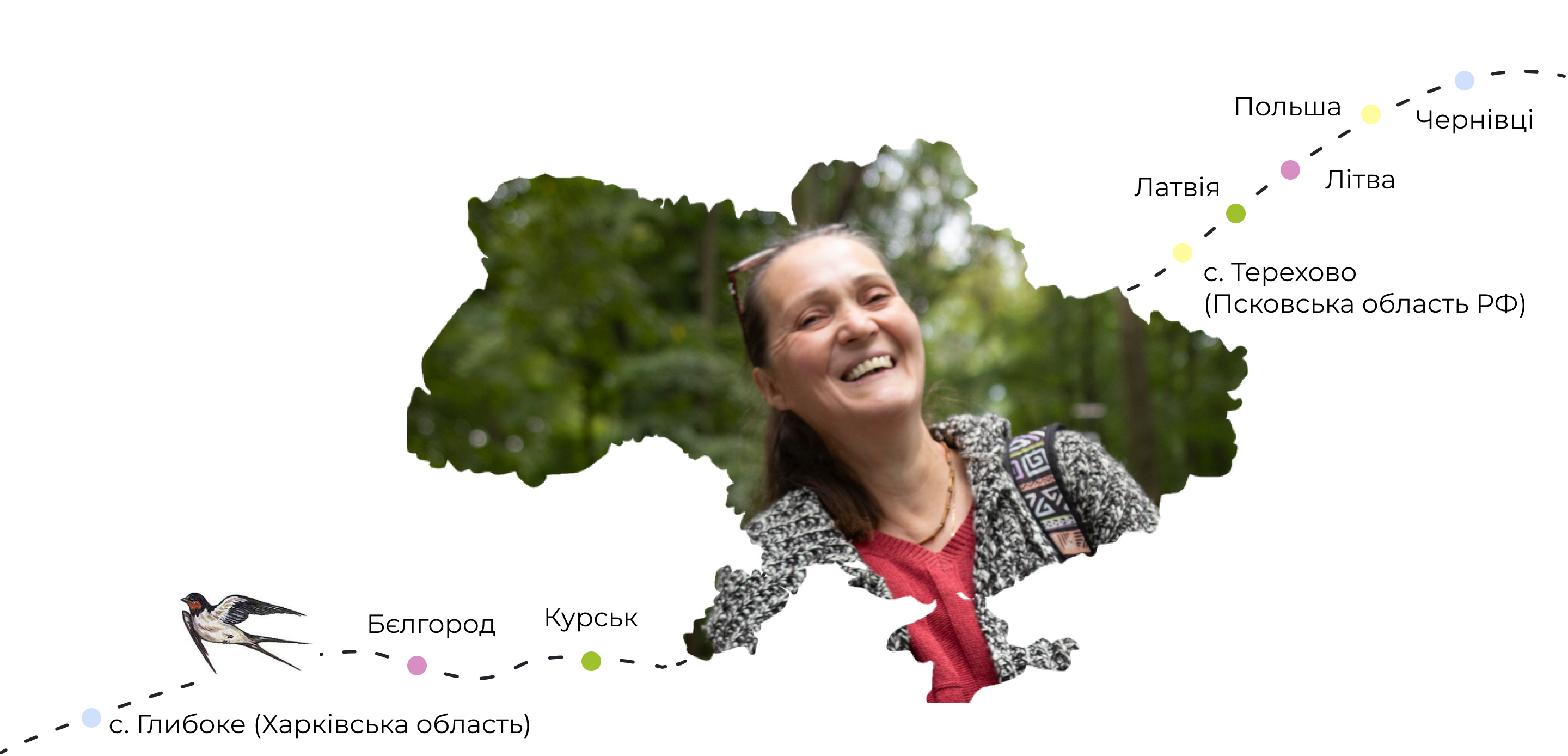

Natalia Pavlova

Saleswoman

village Hlyboke (Kharkiv region) — Belgorod — Kursk — village. Terekhovo (Pskov region of the Russian Federation) — Latvia — Lithuania — Poland — Chernivtsi

Hlyboke village of the Kharkiv district is in the border zone with Russia, so we were occupied in the first hours of the invasion on February 24. My husband and I woke up to a terrible rumble, already there was no electricity, communications or internet because the Russian invaders had deliberately hit the high-voltage line first. We ran out into the street like all our fellow villagers, because no one understood what was going on.

An hour later, Russian tanks and armoured personnel carriers marched through our village, about 100 at two-hour intervals. And so it went for the next three days. We observed these columns, crossed paths with them. Once, with the thought, "I wonder who's going there at all", I looked up and saw a huge Ural truck, driven by an eighteen-year-old black-eyed, black-haired guy. I met his eyes and he had such a doomed look on his face. The next day that convoy was already on its way from near Kharkiv in a totally different condition: with disfigured cars full of "twohundredths"*, ambulances and beaten up tanks.

In those same days stormtroopers started flying over us: terribly loud, very low, about 30 meters above the houses — we could see everything from below on the planes’ bellies. They were flying toward Kharkiv and dropping bombs there — we could hear that terrible bombing very well because we were located at an altitude about 30 kilometres away from Kharkiv. At that moment I realized with anguish that there was no way I could help the people in the city, among whom were my son and little grandson somewhere there — I would not even have time to call them to say "hide in the bomb shelter." At that time I felt intolerably powerless.

My husband, my relatives and I stayed in the village because it was impossible to leave — there was no way to cross the front line, there was fierce fighting.

Back in the 90s, young people in our village, who did not know what to do, began to master construction, some workshops bought generators in large quantities to work. In the first hours of the attack, when there was no light everywhere, these generators saved our whole village. On the eve of the war, I urged my husband, in addition to groceries, to buy gasoline. Because I knew that in a predicament when the money ran out or became worthless, it would be necessary to barter for cigarettes, moonshine, or gasoline. We would take some of our gasoline, take it to those who had a generator, and charge our phones and flashlights.

Exactly one week after the start of the war, Russian soldiers came to our house with their first inspection. That's when they go around the courtyards, search houses, pass something on the radio and talk to the locals. So two Ural trucks with machine guns on top drove up to our yard, and an officer of about 45 years of Slavic appearance got out of one of these trucks.

I'm probably the youngest person on our street, and everyone else is of a respectable age, 60 years and older. He came up to us and asked what we thought about the war. And I asked him in response what they were doing there.

“We have come to free you,” he says.

“From whom?”

“From the Nazis.”

“And who are the Nazis?”

“Nazis,” he says, “are those who are fighting in Kharkiv and because of whom we have many twohundredths*.”

“In 2014 you would have taken us with your bare hands. We didn't have an army. But now you are fighting against the real Ukrainian army,” I told him.

It turned out to be a great revelation to him.

Then there followed more inspections. And among others came the Ossetians, really checking to see what they could take from us. But there was an artificial lake nearby where the prosecutors' summer houses were located, and that, of course, seduced them more. The road to these summer residences runs through our street, so we often witnessed a military Ural driving one way empty and jingling, and then slowly returning tightly laden. Under the pretence of making fortifications, Russian military marauders were quietly looting those houses.

From the first days, our village was deep in the rear, where local order was monitored by the "donbasyatas," as we called the guys who had been brought in from the Luhansk and Donetsk regions. They became our "police" on the Russian side, but they did not cross paths with the Russians at all, lived separately and looked quite different from the Russian soldiers: dressed in green sweatshirts and rubber boots, of all ages, with a kind of doom in their eyes. They made sure that the locals did not break curfew and handed out humanitarian aid to the villagers.

In March, the front line moved closer to our village, and shelling began. It was then that the Russian military began to take people away, both those who had served somewhere and those who had not. I don't know why, however, several of my fellow villagers disappeared and I still have no clue as to their fate.

At the beginning of May, artillerymen came to the village and stayed in our street. They settled in empty houses, because by that time probably about a quarter of the street had already left. By the way, these artillerymen were moving along the road in a rather funny way. The SAU (self-propelled artillery unit) went first — a huge machine that looked like a tank with a cannon, followed by a Niva, then a painted green Moskvich with a trailer, and behind it, a scooter with a Russian flag. They looked like "bears on bicycles," a real circus.

One day I went out into the courtyard, and one of those artillerymen was walking toward me: a tall, handsome man, dressed in military uniform and wearing moccasins. So I asked him.

"What's going on, where should we go, should we hide or evacuate?”

“It's going to be noisy here for a while," he said.

“What do you mean by noisy?”

“Well, you'll hear it.”

“And what will happen next?”

“We're going to take Kharkiv.”

“You haven't taken it in 90 days," I told him, "but will you take it now?”

“Yes, we will," he answered.

“And if you don't?”

“Well, if we don't, another order will come.”

“What order?”

“To wipe it off the face of the earth.”

I froze in shock at these words.

After three months in the occupation, I had no sense of fear. I felt nothing, even though the Russians were constantly firing barrel artillery at Kharkiv somewhere nearby: their SAU and Grads were no more than 500 meters from our house. My husband was constantly criticising me, begging me not to go anywhere. But I didn't go out, I only visited my neighbours, because I needed some kind of companionship. When the debris from the shells started hitting the village itself, but the sense of fear still did not appear, I realized that it was bad.

In mid-May, we noticed that the slope of the SAU near our village had changed. Before, its barrel was at a 45-degree angle, then became almost horizontal. And at night time the sound of a shot and its arrival began to alternate. We can count: 340 meters per second, a shot and literally a second later, the "arrival." They were the ones who started shelling us, so people started leaving the village en masse and in a state of shock, leaving behind everything to their fate: cats, dogs, and livestock, which were now roaming the street. Soon there were only six families left in the entire village, all of whom were helping each other.

In those same days, my husband and I decided that it was safer to sleep in the cellar. Before the war, I couldn't stand it: three meters deep, 14 big steps down. On May 25, about two days later, I was in the yard when I heard something terrible flying. I frantically called my husband and his elderly father, who had disabilities from the Second World War, to the cellar — they had taken him in when it was no longer possible to move around the village. My grandfather stood on the first step, I stood below, and my husband closed the iron door. At the same moment, there was an explosion in our yard. We were genuinely petrified by that wave. And when we managed with difficulty to open the mutilated metal door from the cellar, we saw our windowless house, and in the place of the fence, a hole of about 15 meters in diameter. At that moment I got scared.

A guy, a former drummer, lived two houses away from us. He was left on the farm to feed the animals. So he was sitting in the yard with three dogs, and they were all covered with the blast and killed instantly. We, the six families that were left in the village, came out together and looked at the dead, and we realized that we could not wait any longer.

Opposite us lived a neighbour with a disability who had not gotten out of bed for four years. His wife, who did not want to go, fearing looting of property and waiting for the VSU, came, in tears, "I will go. At least you go down to the cellar, while we lie upstairs and just wait to die. I can't take it anymore."

So, at the same time, all the families still remaining in the village urgently decided to leave. First — to Kursk, to take the disabled neighbour to his relatives. And then they said they would try to go back to Ukraine.

My family was still in a daze after the explosion. My grandfather sat in the yard confused and silent, and my husband walked around completely stunned. And I didn't know what to do next, I couldn't speak to anyone because of the poor connection. There was a dead silence around me after the shelling. Soon I felt a kind of crazy fear as if I had woken up: I could not concentrate on anything and began to shudder at the rustling and banging. But I realized that I could not live in such a state in the village, where I had to be collected and quick, and fear immobilized me.

My son left Kharkiv for Chernivtsi a few weeks after the war began. I finally got through to him the day there was an explosion in our yard — he strictly told me to go to where he was. At the same moment, I ran to my neighbours, who were going by car, asking them to wait for us in Kursk. The next morning I warned the soldiers at the checkpoint that we would be leaving on an evacuation bus, which was taking those who wished to go to the Belgorod region.

We left our home on May 26 — me, my husband of 60 years, my grandfather of 87, and a dog in a carrier. After several transfers, we drove to a refugee camp on the outskirts of Belgorod, where my childhood friend met us and took us in.

In the evening I watched the Russians: they were making barbeque and celebrating a birthday. And I felt so sad after what we had gone through. I couldn't look at them calmly: they came to our country and created all this horror. My friend offered me to stay, but I said that I hated all Russians and that I wouldn't be able to live here and communicate with them. I said, "We will go to Ukraine."

The next day she drove us to Kursk, where all our neighbours were waiting for us — our own people, almost our family. There we spent the night, helped fix the roof because it was leaking, and in the morning we left in two cars to return home to Ukraine.

In the first car went a family: husband, wife and her 74-year-old sister, who was unable to speak after a heart attack and had limited mobility. I was the youngest in our crew, the others were 60, 60, and 79 years old, and our grandfather was 87. He too was no longer able to travel, especially across Europe.

From time to time we made stops but tried to get to the Terekhovo-Burachki border crossing between Russia and Latvia as quickly as possible. In one day we passed through Latvia and Lithuania, got lost in Poland, and arrived in Ukraine the next day. So, a total of eight days passed since we left our village and made it to Chernivtsi.

In the west of Ukraine, I was immediately impressed by the very beautiful houses. After our trip, we had a lot to compare them with: from very rich houses in the Belgorod region to much poorer ones in the Kursk and Pskov regions, to the borders with Lithuania. In my opinion, the Ukrainian barns look much better than the houses of those Russians who live on the border with Europe. And then we got here, in the west of Ukraine, and we saw all this beauty, as when your house is supposed to be the best in the village. Even a pigsty is framed with aluminium lace. We don't have that in the east, everything is much simpler.

The grandmother, the owner of the house where we are staying, doesn't take money from us, so I am knitting socks for her to thank her somehow. Here we are very warmly welcomed, and we help in every way in the garden and the yard. But I still want to go back to my native village: in the morning I get up with the idea "I want to go home", in the evening I fall asleep with this idea.

I would have gone to war, but at my age and in my state of health I probably shouldn't even consider it anymore. I'm waiting for an opportunity to get a job in a hospital as a medical attendant. Just to bring our victory closer and go back to my home.

And on September 12, our village was finally liberated, and in the morning the flag was hoisted over the village council. I cried with happiness. I never thought it was possible to cry at the raising of a flag. I also found out that my dogs that we couldn't take with us were alive. We will be going home soon. We can't do it yet cause mine clearance is underway.

*twohundredths: "Load-200" in Russian military speak means coffins—or soldiers killed

Recorded by Alyona Vorobiova

Translated by Katsiaryna Khinevich

Photographed by Vladislav Yevdokymov