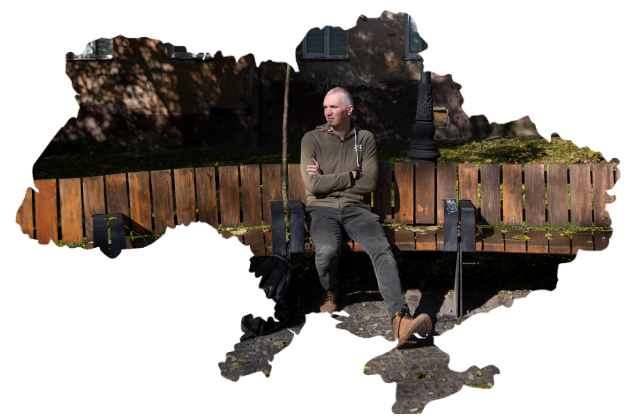

Illia Budko

Musician, member of the band “Мальчик Паж”, music teacher. Lost his job because of the war, and is studying IT

Kharkiv — Horishni Plavni — Lviv

On February 24, at five in the morning, my sister called me; she was in Lviv with her young son and husband. She said, "The war has started." I was like, "What?" Somehow I didn't believe it, I was so apolitical... Well, everything has changed. I went to my parents, and I said, "It's a war, they say. You've heard?" They were like: "Well, okay." And somehow they were very calm and relaxed. And I was like, "Are you guys okay? Let's do something.”

In Kharkiv, there was a church near our house. It was about a 15- minute walk through the woods. And we lived there for a week. There is an aircraft factory nearby and it was very heavily bombed. People of all ages were hiding in the church, I think there were roughly 150 people: some stayed for one day, left, and others came.

There were four of us: mom, dad, me, and my little sister. We took musical instruments with us to the church: dad had a guitar, and I played the cajon at first. But then there were grandmothers there who would get scared because its sound resembled that of explosions, so we ended up with just the guitar.

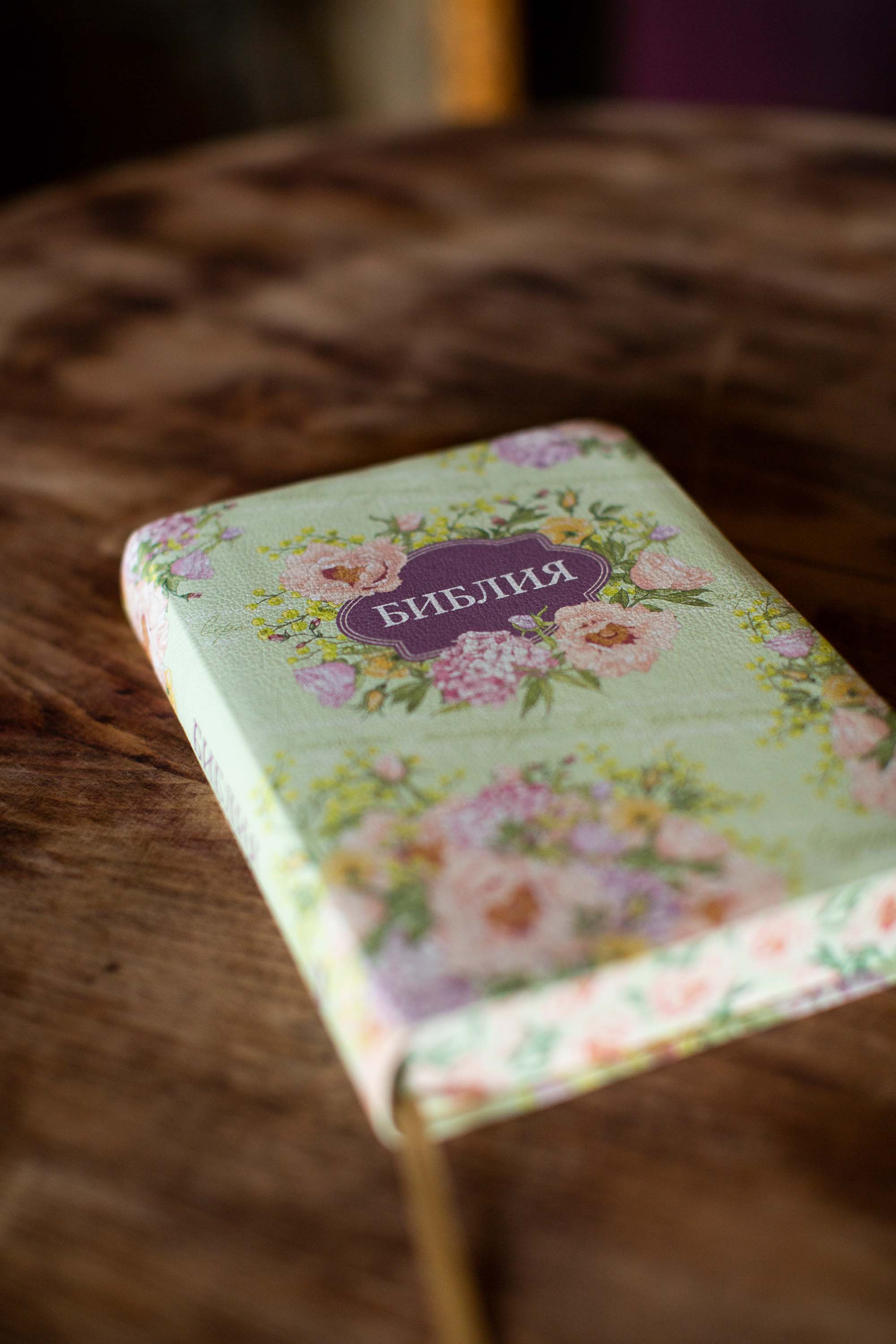

Four years ago my father was diagnosed with cecum cancer. He was still getting chemo when the war started, and it was hard for him... Come to think of it, you're breathing in the dirt in the basement all the time, you're also getting chemo, and you're not eating very much, and already you're losing weight. But he played his guitar all day and he prayed. He has been motivating us all these four years to remain positive.

We stayed in the church until there was a direct hit in the churchyard. Then the pastor called and said: "Evacuate."

My elder sister Nastia said: "At least go to our grandmother, to Horishni Plavni." She and her husband and son went to Poland, and then to Canada because her husband is a Canadian citizen. Even before the war, he was already saying, "When are we going to Canada, when are we going to Canada?" And I hated him for that — my sister and I are in a band together and I adore my nephew. I couldn't imagine how I would live without them.

I didn't understand right away what was going on. I asked my mother: "When it is over, will Nastia come back to Ukraine or will we go to Poland to visit her?" And my mother said, "She's not coming back here." And I sat there crying: I realized, eventually.

We spent a month in Horishni Plavni. We were eating a lot there, because the first week of the war we just had some crumbs, as there were so many people. I remember, someone got some biscuits for the children and I got a bit for myself. I was looking at this little piece and I was so overwhelmed: I sat there and sobbed with gratitude that I was alive, that I had this little piece of biscuit.

We wanted to be useful. Just to eat, to shit, to depend on my grandmother, well, that wasn't what we wanted. My father also lost his job because of the war, and we looked for some jobs, at least to sell ham or something, but there were no options. You walked around and saw that everything was closing down, everyone was leaving.

Half a month later, I got the idea to do a song to the poetry of Vasyl Symonenko, the poem "Swans of Motherhood". I hadn't done that before: not write my own lyrics, but write music to the existing lyrics. I understood that we couldn't record it in Horishni, there were no music studios there.

In general, I thought: "Well, when the war is over, then we'll record it." I thought, as Arestovych had said, that it would be possible to return home in a month. To the last, I thought that I would return to Kharkiv, together with my former sound engineer we would make a track, just as we used to do during all these years.

But my father said: "Come on, get your ass up, let's go to the West of Ukraine, let's make the song." I was very annoyed at that moment: where to go? I wanted things the way they used to be! And in my soul, I felt (or you can say in my spirit) that I had to go. You know, it's kind of about hearing the voice of Jesus in your heart calling you to act. Physically you don't want to at first, but spiritually you know you have to act, and the body is already adjusting to the spirit.

This was the first time I visited Lviv. The architecture here is so cool. In Kharkiv, you see some nice buildings, and you savour them. But in Lviv, it's a pure concentrate: gothic and graffiti, just the way I like it. It's a real pleasure to make video clips in such a city. Somehow I immediately switched to Ukrainian when we came here, and the songs started coming in Ukrainian.

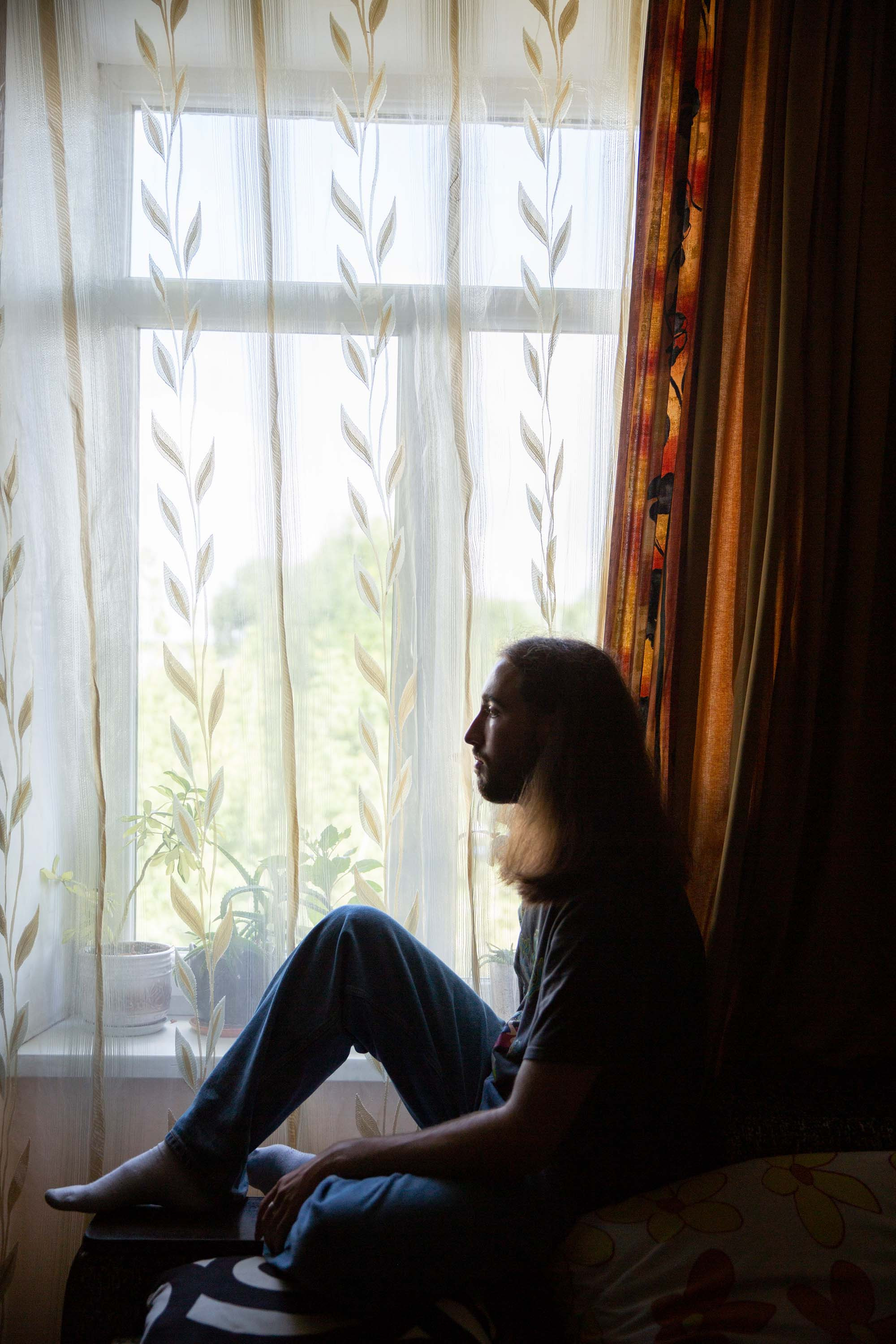

I've been here for almost three months, now I'm alone. For two months I was with my mother, father, and younger sister, who are now in Germany. They went because of the medical treatment as my father was prescribed even more expensive medicine. But what we really need is a miracle. It was probably the shittiest day of the war: we had already been in Lviv for a month, and my father's tests came back. It got even worse: a recurrence, metastases.

There is a good term in the Bible, I remember it in Russian: "separate the precious from the worthless." And this is about our situation: it is the most worthless, can’t get any worse. It's the ultimate horror. And when the situation is so shitty, you can get the most gold from it. You have to not waste this opportunity. Because really, what else is there to do? It doesn't come right away, I've been training myself to "separate" for four years now.

I happen to have experienced a lot of pain in my life, in my twenty years. I had never known such pain before the situation with my father. But when you understand your mission and why you should live, it is very motivating to carry on in spite of this horror.

And now I'm writing a new song, already being put together. It's about Joseph, you know, that person from the Bible. If you read his story without knowing the end, it seems like that's the end of Joseph. His brothers plotted to kill him and you think, “He's going down.” Then they threw him in a pit — he's going down, then they sent him to Egypt — he's going down. Every stage — there are four or five chapters — you think, "That's a total shithole." But when you know what the ending is, you're like, "Oh, that's interesting!"

And so it is here: our whole life is very hard. But if you believe that you’ll end up winning, you're like, "Okay, this is at least a very interesting film."

Recorded by Olha Vasina

Translated by Katsiaryna Khinevich

Photographed by Anna Bobyreva