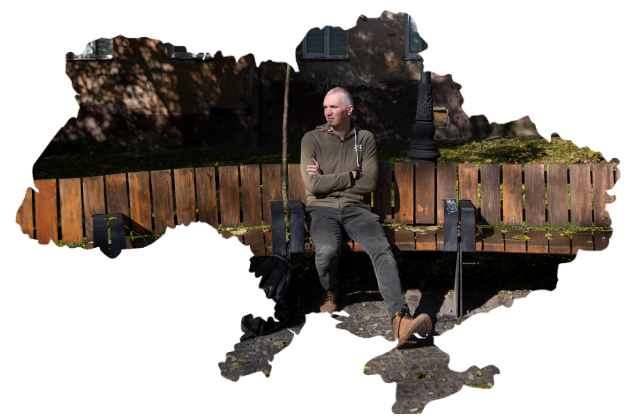

Mykyta Demenkov

CEO of rap.ua, the Sneaker Mate chain of dry cleaners and the co-founnder of NGO Some People.

Kharkiv — Kyiv — Kharkiv — Dnipro

On February 24, my day started with a friend waking me up by the fifth call and telling me that a full-scale war had begun. I replied, "Brother, give me five minutes to gather my thoughts." When I hung up, my window frame started shaking, I could smell something burning, and I realized my friend was not kidding me.

I read Telegram channels, smoked ten cigarettes, filled up on water, bought some medicine at the drugstore, and went to the supermarket. I realized I would spend half a day there to buy something, so I left for my Sneaker Mate office. At ten in the morning, the whole team and our friends were already in the office — deciding what to do.

The first thing I saw in the lobby of our office was a "kindergarten," as everyone came with their children. In everyone's eyes, there was confusion and aversion to the situation. You try to make a joke of it, to try to keep yourself in tone, but at the same time tanks are coming down your street. The weather, however, was clear — the sun was shining.

Some of our team left, but eight people stayed to live in the basement of Sneaker Mate. Soon we started volunteering like everyone else — collecting money through social media to buy groceries and take them to people staying in the subway.

Those who stayed in Kharkiv were the ones who made that decision for themselves. Our friends who left put up a fight with us, but that's how we decided. Some had relatives who were staying here, for others Kharkiv was their hometown, and they didn't want to abandon it. I felt responsible for the rest of the team and wanted to help in some way.

On March 2 we were taking yet another humanitarian aid to the subway. What was happening there could be described as hell ... You had already accepted the war and your place in it, had somehow reconciled with your fears, had agreed with your brain, but the subway is a story that knocks you out of your seat. People have lost everything, from their homes to their families... It's impossible to come to terms with. You had your home, your life, and now there's no life, no home. And for me, that's the scariest part is not knowing what the future holds.

I am a mentally stable person, so I tried to just work and help, not paying attention to what was going on. That worked until March 2, when a rocket hit our office at the Palace of Labor. With my friend Slava, I was standing in the courtyard, recording a video message in which I was reporting on the money I had received and spent. Then I heard a whistle — a second later a rocket hit the Palace of Labor. A second one. We ran to the basement, I don't know why I didn't turn off the video recording on my phone.

The next day, the footage was in the news all over the world, from Australia to the United States. I found it especially interesting to watch myself on Japanese television. The video and the attention to it helped create a sizable volunteer team. But most importantly, everyone survived. Only Slava broke a finger, as the blast wave blasted out the door and hit him.

I was being talked into leaving Kharkiv from day one, but I couldn't. My parents were in occupied Kupiansk, the team lived in the office basement, for me and my wife Kharkiv is our hometown. We used to travel a lot for work and lived in different cities for months. And now, when we had finally settled in Kharkiv — they took that away from us. The rage I felt at that time was overwhelming, and it hasn't disappeared yet.

In March, we started getting phone calls from acquaintances and friends, telling us that it would get even worse in Kharkiv. There were four of us guys and four girls. We talked to the guys and decided to stay. We thought of persuading the girls to go somewhere else. When we told them about it, they looked at us as if we were fools and said, "We're not going anywhere.” We said, "You understand that you could be killed, sexually assaulted, and it could happen that we wouldn't be able to help.” They calmly said, "Yes." Our girls are very strong, we are very proud of them.

We left Kharkiv 40 days after the start of the full-scale invasion. The volunteer headquarters was getting bigger, I had a lot of communications to do, and it was getting harder and harder to solve all issues locally. I took part of the team to Kyiv and stayed there, while some went to Lviv.

The first response was one of shock. You come to the capital, and it's living. The contrast is incredible — as if you were not even on Mars, but somewhere on Mercury. People smile, places work, the sun is shining, and more people are coming all the time. At first, it was difficult to coexist with this — the dissonance was unbelievable. But then I got used to it, and after a while, I realized how good it was when people could live a normal life even during the war. I do not understand those who condemn it. It's true, that some things in that "normal life" may seem excessive, but I'm not talking about them now.

I stayed in Kyiv for a few days and... returned to Kharkiv. I couldn't help but go back there, especially because my parents were in Kupiansk. I argued with every one of my friends. I tried to explain to them why I came back. I even said: "It is cheaper in Kharkiv, there is a place to live." And they would answer: "Old man, prosthetics and funerals are more expensive than renting an apartment."

We went to Kharkiv with a colleague in an empty carriage, there were not many people who wanted to come back at that time. When we arrived, we realized that there were some new sounds (we had gotten used to air defence and air strikes before, but now something else had been added) and that the shelling had become more frequent. We worked and continued our volunteer work. But after a while, I decided to go to a safer place. The main reason was my wife Yulia, she would never leave without me. And also the cat — he also needed to calm down.

We went to Dnipro. We have one of our offices there. We found an apartment almost immediately because of our acquaintances. The move was not hard, we live normally, and we continue to work.

I travelled a lot during peacetime and used to change cities and apartments. But I want to do it by choice, not because my hometown is being shelled by invaders. That's my main distress. I usually move from one city to another because I am working, contributing to my country's culture, and doing creative work, not because my home is destroyed.

Until February 24, no matter where we were, my wife always wanted to go back to Kharkiv. We are from Kupiansk ourselves, but Kharkiv is a real home, especially for her. Now, this opportunity has been taken away from us, and we are very much waiting for the moment when we will return, rebuild the ruined office and start living the usual Kharkiv life.

Recorded by Misha Pravilniy

Translated by Katsiaryna Khinevich

Photography: Arsen Dzodzaev