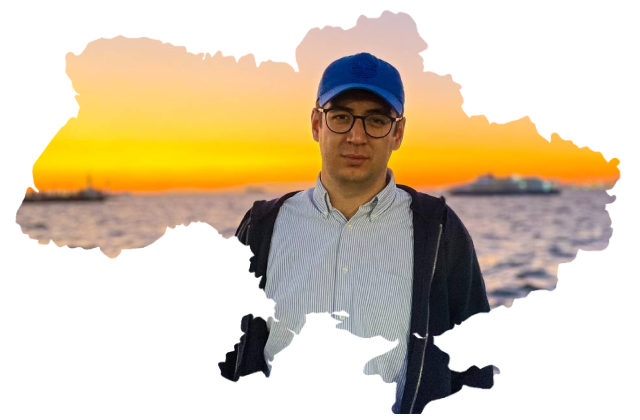

Kostiantyn Kaposhylin

Lawyer in the field of military law, poet

Kherson — Lviv

I am a native citizen of Kherson. I was born in this city and lived there for 38 years. Before February of 2022, there was no war in my life, the one that I’d see with my own eyes.

I remember my February 24 very well. I guess like every Ukrainian. This day started with the sound of an explosion. I live near a bus station, which is very close to Chornobaivka — a village in Kherson Oblast, where the airport is located. The first explosions were there.

So I woke up because of the noise. I took my phone, opened Ukrainska Pravda (social and political Internet media) and I read that the war had started. I woke up my wife and my daughter. We started packing things quickly. The first thought was that we had to buy food for the child, at least for a few weeks. Because I understood that we could stay in the basement or at home for a long time, without the possibility of going out to a shop.

I stood in a long line and bought everything we needed. Around 8:30 I came back home. Then I went to my mother, after that — with her to the bank to withdraw money.

Later, I took my mother home, stood in a long line for petrol. The petrol station was located on the way out of Kherson, near the Shumenskyi city district. Further there was a field, a private sector and after it — Chornobaivka. When we were filling the car, we saw russian helicopters flying there and launching airstrikes at the airport.

There were 50-70 cars at the petrol station. All of us got out of our cars and saw the shelling with our own eyes. Later on, I came back home and actively read the news. My family and I stayed at home, we didn’t know how long it could take and what we would do next.

At that time I thought that russians needed a few weeks to come from Crimea to Kherson, that there would be no blitzkrieg. We hoped that the Armed Forces of Ukraine would put up strong resistance on the approaches to Kherson. But the next day we understood that russians were rapidly approaching the city, so we moved from the Tavriiskyi district to my mother-in-law, because there was a bomb shelter in her five-storye building. Unfortunately, I couldn’t stay with my family as my mother-in-law had three cats and I’m allergic. That’s why I settled nearby.

We spent three days in the bomb shelter. There were 70-80 people: women, children, elderly people, men. We heard sounds of explosions on the Antonivskyi Bridge, though at that time we didn’t know yet what they bombed. We went to the shop in short dashes. We didn’t leave the district, almost all the time we stayed in the shelter or at home.

On March 2 russian occupation troops entered Kherson. At 8:30 we woke up in the bomb shelter. We went outside and saw that from the side of the bus station (which is the entrance to the city), along the perimeter, stood groups of russian soldiers. It was a horror. We understood that the russians had occupied the city.

Before the beginning of hostilities, I worked as a lawyer at the Center for Assistance to Participants in the Hostilities in the East of Ukraine. In 2015, I wrote a book about the war in Donbas that was called The Tower. Also, about half a year before the full-scale invasion, we registered a large veteran union of ATO participants in Kherson.

So, when the russians entered Kherson, I was afraid that they could be interested in me as a Ukrainian activist. That’s why I didn’t go to the place where I was registered. I lived in another place as I was afraid that they could come and get me.

Firstly, the call of the Ukrainian authorities to leave the city pushed me to the decision to leave Kherson. Secondly, the desire to get out of that awful Groundhog Day in the occupation. Thirdly, the safety of my family, of my child, as it’s dangerous in the occupied city.

There were explosions from time to time, active hostilities could start. And, you know, 99% of Kherson citizens were waiting for them. Because that would mean that the Armed Forces of Ukraine came to liberate Kherson. And absence of civilians would make our military’s job easier.

I remember once, in April, I decided to stay for the night at home and invaders started getting into the building. In the chat of the Union of the Owners of Multiple Houses it was written that orcs were getting into the fourth entrance, trying to tear down the door. I thought then: “Well, that’s it, they’re coming after me!” I dressed up and waited. It turned out that the russians got a person from the fifth floor. At that time it reminded me of the events of 1933 that Remarque described: when Germans from the Gestapo arrested people in their apartments. At that moment, I fully experienced that feeling.

In the beginning of April my family and I tried to get out of Kherson but the invaders blocked the road. Our next attempt was in mid-April — also unsuccessful. And only on May 4 we managed to leave Kherson and come to Lviv: my daughter, wife, mother-in-law, my mother, grandmother. After that, the whole family, except me, went to Bulgaria.

In my case there was no uncertainty ahead. I knew that I’d have a job and a place to live in Lviv — I took care of it beforehand. I knew that my family would go to Bulgaria. Being in the occupation, thanks to my friends and acquaintances, I managed to solve all the issues concerning my future.

I remember how scary it was to leave. Because that meant dealing with representatives of the russian occupation authorities. I still remember the eyes of the person that stopped us at the checkpoint. At that time my only thoughts were that I wanted to get out, to feel freedom. Not to get under shelling and move my family to a safe place.

In Lviv I didn’t face a problem of lack of money, absence of work or a place to live. Instead, I had some psychological difficulties. I got out of the occupation where I had stayed for 2,5 months. The lingering feeling of suffocation was replaced by the desire to finally feel freedom. It seemed that I simply couldn’t get enough of it.

First two months of my life in Lviv I really wanted to travel, walk, find new acquaintances. I participated in everything, went to poetic evenings, I wanted to feel alive as much as possible. Now I think that it’s not really the right decision. There should be balance in everything. And at that time it was a bit lost. Now, I’ve already restored the balance.

Citizens of Lviv accepted me absolutely normally, there were no conflicts or negativity. Here I communicate exclusively in Ukrainian, although my whole life, when I lived in Kherson, I spoke russian.

In Lviv I found the possibility to earn money. I believe that the first thing to take care of in a foreign city is finding a job. And not thinking that maybe you can just sit out somewhere, get money from the country and that’s it. A person must recover from what they experienced and start living on, providing for themselves on their own.

My weekdays now — work in a lawyer's office and help military personnel in the legal field. There’s really a lot of work. On weekends, I try to relax creatively. I found the same refugees from the south as me, creative people, and together we organized poetic evenings Sweet Review. We hold them once a month and gather money for the needs of the Armed Forces of Ukraine in this way.

What’s home for me? It’s a place where I feel good. If I’m asked if I think of Lviv as my home, I’ll say yes. Kherson is a city where I was born and have lived for 38 years. It’s a city that I love. Is Kherson my home? Yes, definitely. But I can’t live there now.

Now a lot of people suffer, in Ukraine and abroad, should they come to their hometown? It’s a difficult moral dilema. I believe that everyone can have a city in our country where they feel better: in Odesa, Kharkiv and so on.

Maybe I’ll come to Kherson when it’s liberated. I’ll go to my hometown, to my small Motherland, where I was born, where my child was born. But for now I want to live in Lviv.

I believe that the most important thing for us, Ukrainians, is not to leave our country. To stay somewhere abroad, personally I wouldn't like to. I want to live in my country, help it grow it. Especially now, when it goes through such difficulties.

When I found out about russians leaving Kherson, I had two emotions.

The first one was joy. Because, to be honest, I was sceptical and thought that the city would not be liberated so quickly. I thought it would be February or March 2023. But I never expected Kherson to be de-occupied in November. And when the city was liberated, I felt an incredible sense of relief. There was a feeling of happiness comparable to the one I felt when my daughter was born.

The second emotion was a sense of responsibility for my own city. Because as a lawyer I am involved in solving many legal issues related to Kherson. Now there will be many new requests from people who survived the occupation. We will be collecting information about traitors, collaborators and accomplices of the russians. The first submissions have already been coming in and we are beginning to process them.

I am aware that my professional activities will now be devoted entirely to ensuring that all lovers of the "russian world" are held accountable under Ukrainian law.

Recorded by Valeriia Merenkova

Translated by Volha Mikhnovich

Photographed by Anna Bobyreva