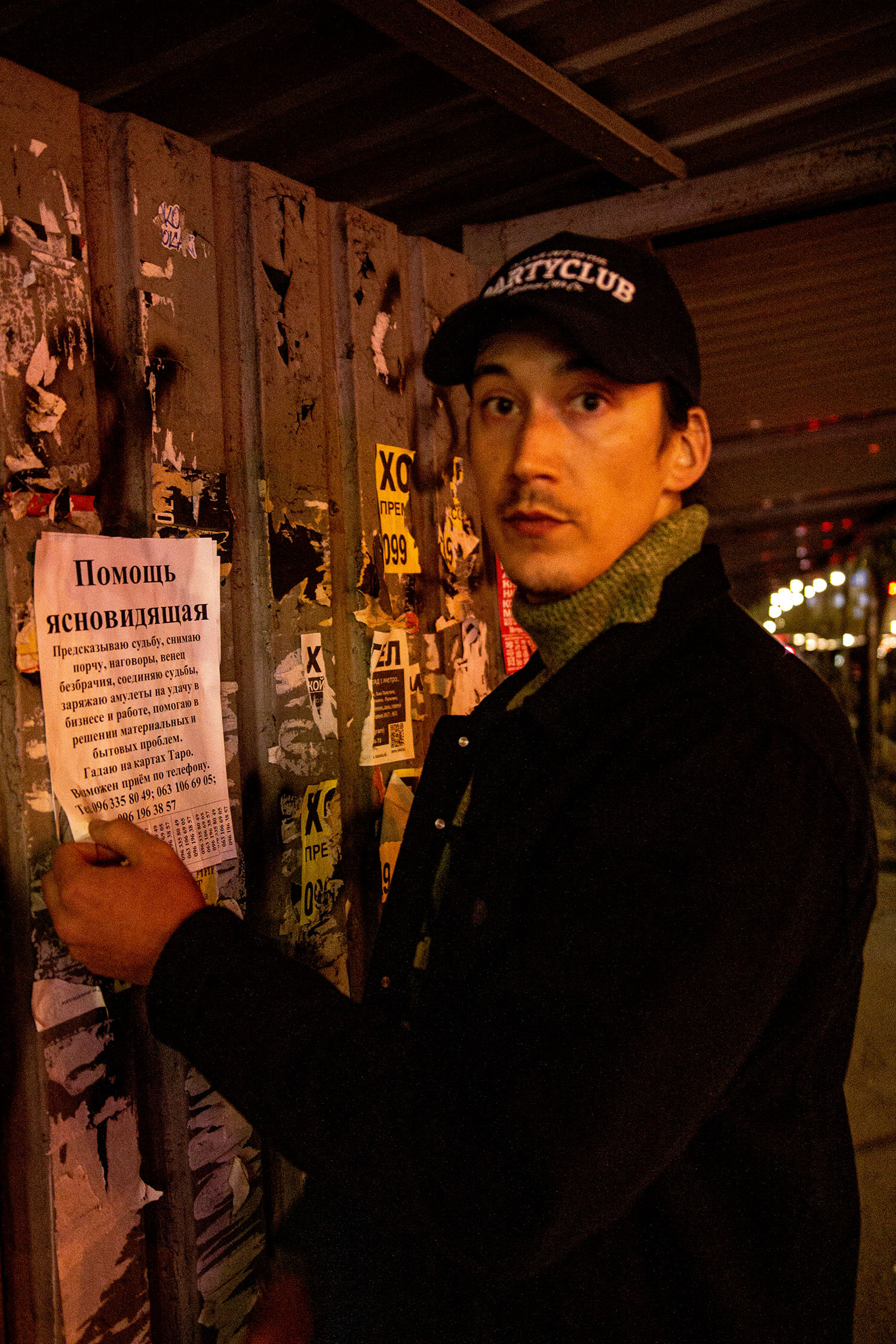

Aleksandr Chudnovec

Administrator of Promodo Hub, designer at Promodo Academy

Pervomaisk (Luhansk region) — Crimea — Russia — Belarus — Kharkiv — Lviv — Chernivtsi — Berehomet (Chernivtsi region)

I come from the small town of Pervomaisk in the Luhansk region. When I finished school I went to the Luhansk State Academy of Culture and Arts to study directing and since then I started living in two cities: on weekdays in the student dormitory in Luhansk and on weekends, I returned home to Pervomaisk to teach dancing.

In April 2014, something obscure started in Luhansk. The then Rector of the Academy gathered all of us together and made a speech, "You are studying culture, politics is none of your business!" And he warned us that anyone who went to the Maidan would be expelled at once. When the separatists seized the SBU building in Luhansk, all the students were dismissed from the summer session with "automatic passes" and sent home.

On July 29, the missile attack on Pervomaisk began. That day, my parents, my brother, his wife and his little son, and I organised beds in the basement. For about a month we hardly went out.

At the end of August, we were told that there was a 'green corridor' for civilians, which my brother with his family and I used to leave Pervomaisk for Crimea. To get there, we stood waiting at the border in Dzhankoy for four days.

We rented a flat in Yevpatoria. There was no work, so we applied to the refugee protection programme because it was no good to be without money. That's how we ended up at the Artek camp. There "obliging" Russian representatives quickly formalized refugee status for everyone who was as confused as we were. They required almost nothing from us, they did everything themselves: they printed photos, collected documents, and filled out the forms so that we could get our passports as Russian citizens within six months.

I was 19 at the time, and then I had not considered at all whether or not to get a Russian passport. The situation was too confusing. Some people only now, in 2022, have had an insight into what really happened in 2014. Back then, nothing was clear: what was bad, what was good, who fired the shots, where the shots came from and why. And based on that situation, we had no alternatives.

In Simferopol, there was an abandoned base of the Ministry of Emergency Situations in the mountains. The Russians put up huge tents there for 20-25 people each and started settling the displaced people there. We were fed three times a day, and the volunteers were quite friendly about everything, offering a choice of cities across Russia where we could move to. At first glance, it seemed cool: here we are feeding you, sheltering you, acting responsibly for you, sympathising with you. We chose Tula because it is not far from Moscow.

A week later something started to happen: a bus arrived, loaded everyone, and left. Then another one picked everyone up randomly and take them somewhere. Another bus took us to the village of Ikonki in the Tula region, to a private recreation facility. There they started filling out the same paperwork for us that we had already done for us in Artek. The process of applying for Russian citizenship began to drag on.

My mother had a friend who moved to Moscow a long time ago. I called her: "We are in the Tula region, but I don't want to stay here.” She eagerly invited me to stay at her place.

In Moscow, the situation was the same as in Crimea. In the news, they wrote that special conditions were provided for refugees, even a slightly higher salary. But in reality, the money was not adequate for a living wage in a big city.

I stayed in Moscow for two months. Then I went to my girlfriend Nastya, who ended up in Belarus with her parents. I looked for a job, but the correlation between my salary and, for example, the rent price for a flat was disastrously disproportionate. It was impossible to live on that money at all.

Then, in early December 2014, I decided that I would go to Kharkiv, to my cousin who was studying there. So three months after I left my home in Pervomaisk, I found myself in Kharkiv. I stayed there until 2022. I worked, and started a family with my girlfriend Nastya — after we moved to Kharkiv, we got married.

In the Luhansk region, the approaching war was well sensed - people understood that sooner or later it would happen. And in Kharkiv, some people were panicking, while others were as relaxed as possible. Probably I would refer to myself as “relaxed”, because till February, 24th I considered myself the rugged wolf because I had already gone through all that. I did not prepare in advance because I knew what to do if the bombing started.

It was the morning of February 24. And when my wife got a wake-up call from her father, I just felt déjà vu — all the same for the second time. I woke up calmly, realising that nothing too extensive would happen that day and that the Russian military would not wipe out Kharkiv because it could not be done in one day.

I had a separate shelf in my flat with my documents, money and passports on it. First of all, I threw them in my backpack along with my laptop. I wore a waist bag because if we had to go to the basement, we needed to have a power bank, phone, keys, etc. With Nastya, we also packed suitcases (as when it would be possible to move out, we would be leaving the city) and went to the shop to buy food.

For the first four days, I didn't go out unnecessarily, even when we had poor reception in the basement of our high-rise on Gagarin Avenue. But one day I woke up to a flood of messages saying that a colleague at work had not got through to me. I called him and heard, "I'm on my way to Odesa, you have five minutes to pack, provided there's no room in the car for your things.”

So Nastya and I took only a backpack with our documents and sleeping bags and drove to the vault at the Promodo office, where we stayed for another five days, until 4 March, when a fighter crashed the Unifecht university sports complex, which was very close by.

Before that, the mood in the office was that no one was going anywhere. I mean, I asked everyone:

“Are you going away?”

“We're not going anywhere!”

“Are you going anywhere?”, I asked again.

“We're not going!”

After a bomb landed quite close by, everyone had a dramatic change of heart. A colleague of mine told me that she had a friend in the small town of Berehomet in the Chernivtsi region. My wife, my friends and I went to stay with this friend. First, by train to Lviv, and then by car to the destination.

Despite the fact that Berehomet is a resort town, the people here are very cool. Many would let those who came here live in their houses, saying, "Just live here, take care of the house, and pay only for utilities." That's what happened to us too.

Since leaving Kharkiv, I have been working remotely all the time with the Promodo Academy team: designing photo and video content, running courses, etc.

I would not like to move to a big city, for example, Kyiv. In any case, I want to return to Kharkiv, and I am not ashamed to admit that I am scared to move there for now. I feel good when there are people around and they need to be comforted and entertained. But I'm not the kind of person who goes to get food under explosions. And I don't hide it.

If Kharkiv remains a frontline zone for a long time, I would not consider returning. I would rather go to work abroad. For example, to the UK — to earn money and come to Kharkiv to open my own workshop. Because I have had the idea of sewing things for a long time. And I have also seen statistics that last year the workers abroad transferred nine million dollars to the state treasury of Ukraine. This is a crazy amount, which could also help at the front and bring us closer to victory.

Recorded by Alyona Vorobiova

Translated by Katsiaryna Khinevich

Photographed by Vladislav Yevdokymov