Muslim Umerov

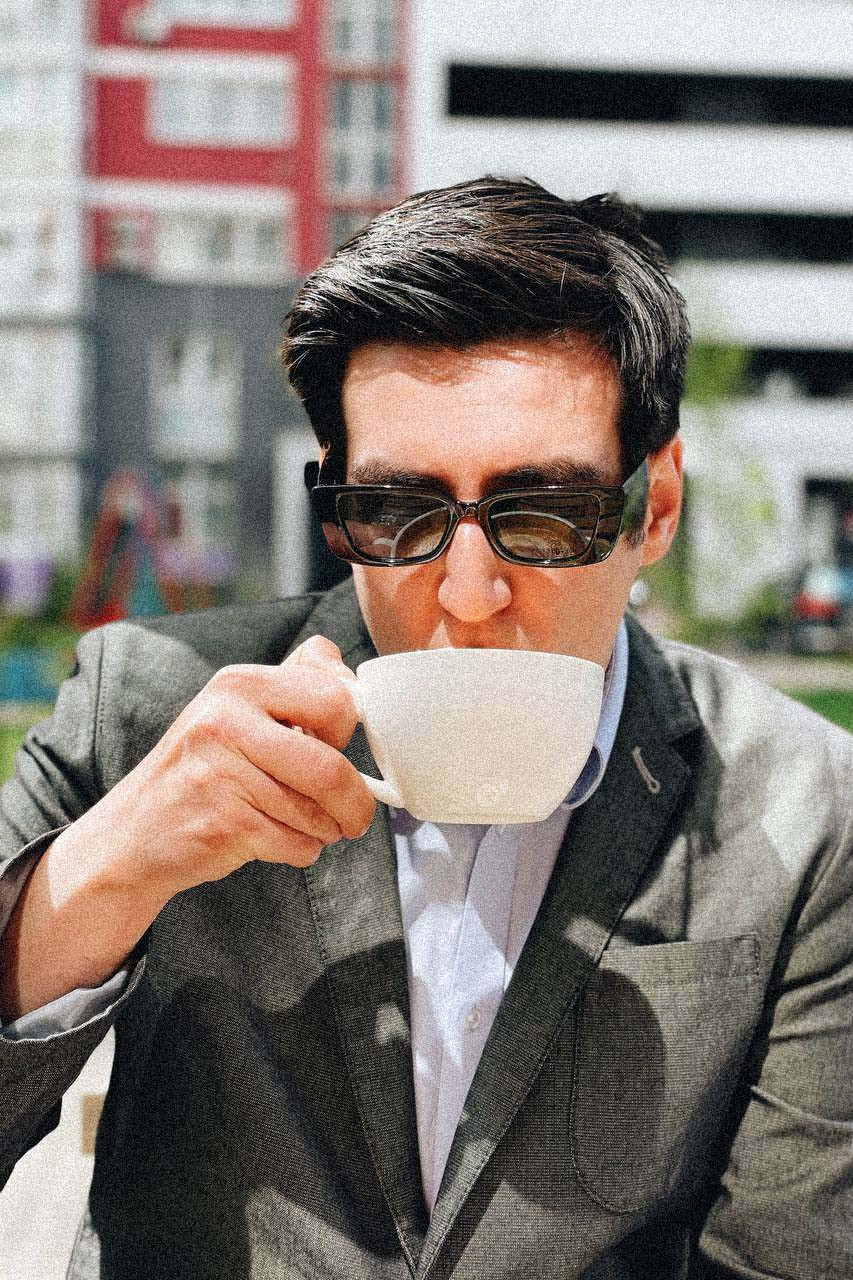

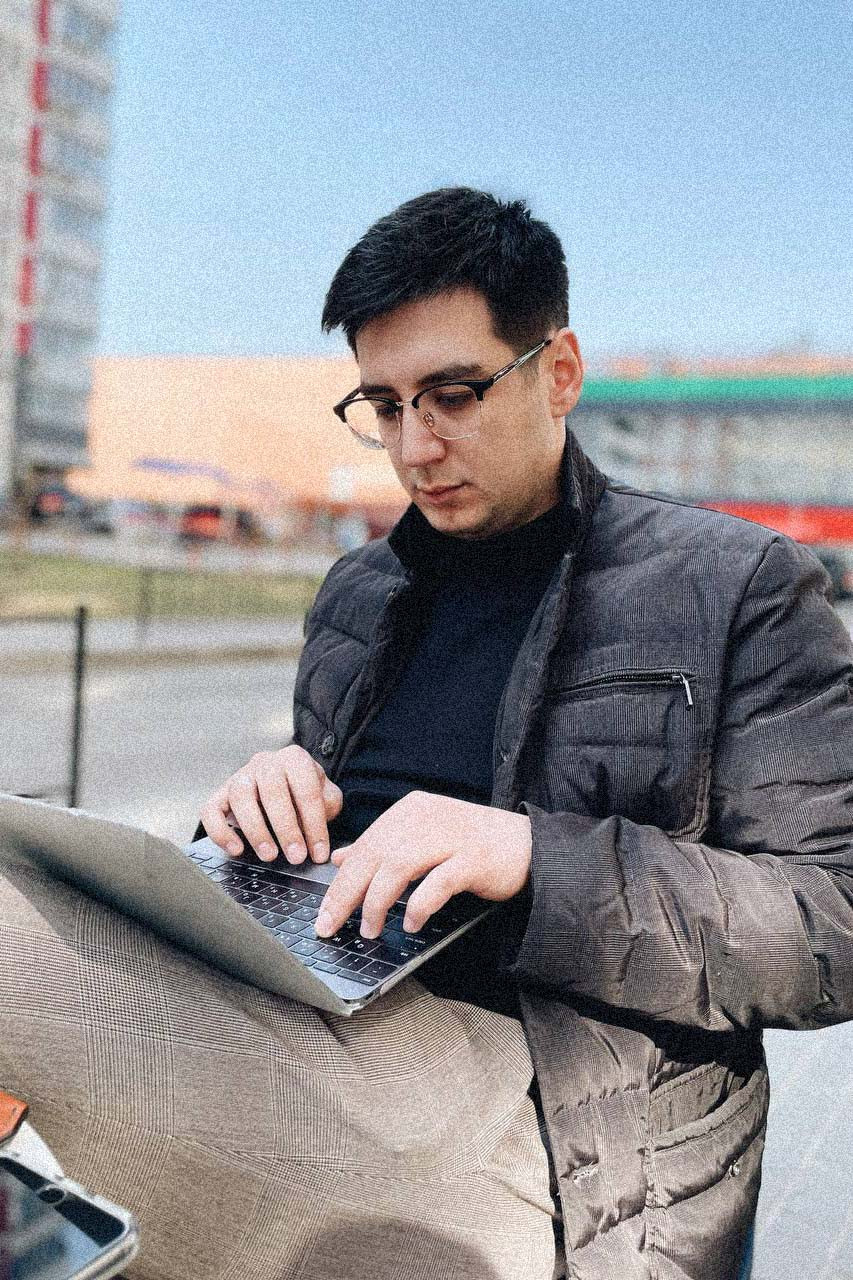

Journalist, producer

Simferopol — Kyiv — Yahotyn — Khmelnytskyi — Kyiv

I was born in Yevpatoriia to a Crimean Tatar family. In 2014, when the occupation of Crimea began, I was a second-year student in Simferopol at the V. I. Vernadsky Taurida National University. I was interested in journalism, and almost immediately, in March, I started streaming for the local independent media about the first unmarked military personnel who started appearing in Crimea.

Then I had to choose: to learn to naturalize in that environment or not. I chose to leave and immediately moved to Kyiv.

Eight years later, on February 23, around 8 p.m., acquaintances of our family told us that a full-scale invasion would probably begin the following morning. My wife and I went to my parents' house to tell them to pack their bags and to spend at least that night together. Before the war, my parents did not believe the predictions of a full-scale invasion, but surprisingly, they quickly packed up and came to our house.

Later that night, news began to appear online that the Boryspil airport, and then the airport in Dnipro, had been closed, so the assumption of war was reinforced. We stayed up until two in the morning. Then I fell asleep and woke up to a cat jumping on my head. A friend had been calling me, but he couldn't get through and called my wife: he said he was watching Putin's address. And just at that time, the explosions started.

For a while, maybe for five minutes or so, there was some kind of shock. My parents, my wife, and I were looking at each other. Everyone understood everything, but no one said anything, we just turned on the TV. We decided to buy tickets to Lviv first, but I had a premonition that we were not supposed to take a train, as it could be blown up.

At ten in the morning, I suggested to my father and wife (my mother refused) that we at least go downstairs and walk to the store. We went and bought water and something else. At the same time, I was surprised by the people going out for a run. In all the panic, everyone was leaving the neighbouring houses, loading their cars, and still, some decided to go for a run.

We spent the first night in the basement of our house, where an enormous number of people had gathered. As usual, when you live in a high-rise, you don't know all your neighbours. So it was unclear who was your neighbor and who might be a member of a sabotage and reconnaissance group. We all armed ourselves with knives, hammers, whatever we had. We were on guard, keeping vigil.

Three days went on like that, and then I got a little scared for my parents. In our family parents usually make all the decisions, but looking at them, it was clear that we had to decide for ourselves. So my wife and I took matters into our hands.

I left Crimea during the occupation, and I had to move again. After eight years in Kyiv, I got a sense of comfort, and it was hard to give it up. First, we went to visit friends in Yahotyn near Kyiv. It took us a long time to get there because we couldn't find a taxi, and we didn't have our own car at that time. I called all the taxi drivers I knew, everyone who had a car. Many were reluctant to go far or said they wouldn't go anywhere, or would only go with their family.

In the end, we called Uklon and went with a man who was on his way from Kharkiv to Kyiv to go to the front. He said his wife didn't know about it, he just wanted to see her, give her a hug, and go to serve.

We rented an apartment in Yahotyn, and we stayed inside for three or four days. During that time my friend Emil set up a volunteer headquarters to evacuate women and children from Crimea. A little while later they started evacuating people from different areas.

Our community — myself and my colleagues — also set up a headquarters, and we teamed up with Emil and started taking people not only to western Ukraine but also to Turkey. When that wave subsided, we started sending food and first aid supplies to those in need, and we also collected some money for the military.

In Yahotyn I did not feel as much panic as I did in Kyiv. Only military planes were flying low because there was a military base somewhere nearby. I hope it is still there.

Several times we encountered Territorial Defence Forces. These are the kind of neighbourhood things that exist even during the war. We lived in a residential complex where they had these houses built specifically to rent to visitors in the courtyard. Neighbours who lived next door, in peacetime, would write complaints against the owners who rented out their homes. We would turn on the lights in the evening, but we would cover the windows with a blanket or something. And two or three days in a row these neighbours called the Territorial Defence Forces. I went out to introduce myself, show my documents, and ask, "There's a three-story apartment building across the street, there are lights on there too, why don't you go to them?"

One day the Turkish channels invited me to go on the air and tell them what was going on in the place I was. I went to the main square and just caught the moment when the Yahotyn Dairy Plant started handing out its products for free. For the Turks who were watching the broadcast, it seemed unusual — they didn't understand why a private business would help. And I explained how the people really came together.

Soon we decided to go to Khmelnytskyi. We took the Yahotyn-Kyiv train, the most "wrecked" one the kind that I probably last went on in Crimea nine years ago. When we approached Kyiv, the atmosphere inside was as if the walls of the train were falling apart: everyone was in shock, fear in their eyes. Everyone was looking around to see if there was anyone who seemed suspicious. We kept paying attention to one person, for some reason drunk — we thought it was a little strange. This person would go into that train's toilet, and my father and I would check afterwards to see if he had thrown any explosives in there. For some reason, we had such thoughts.

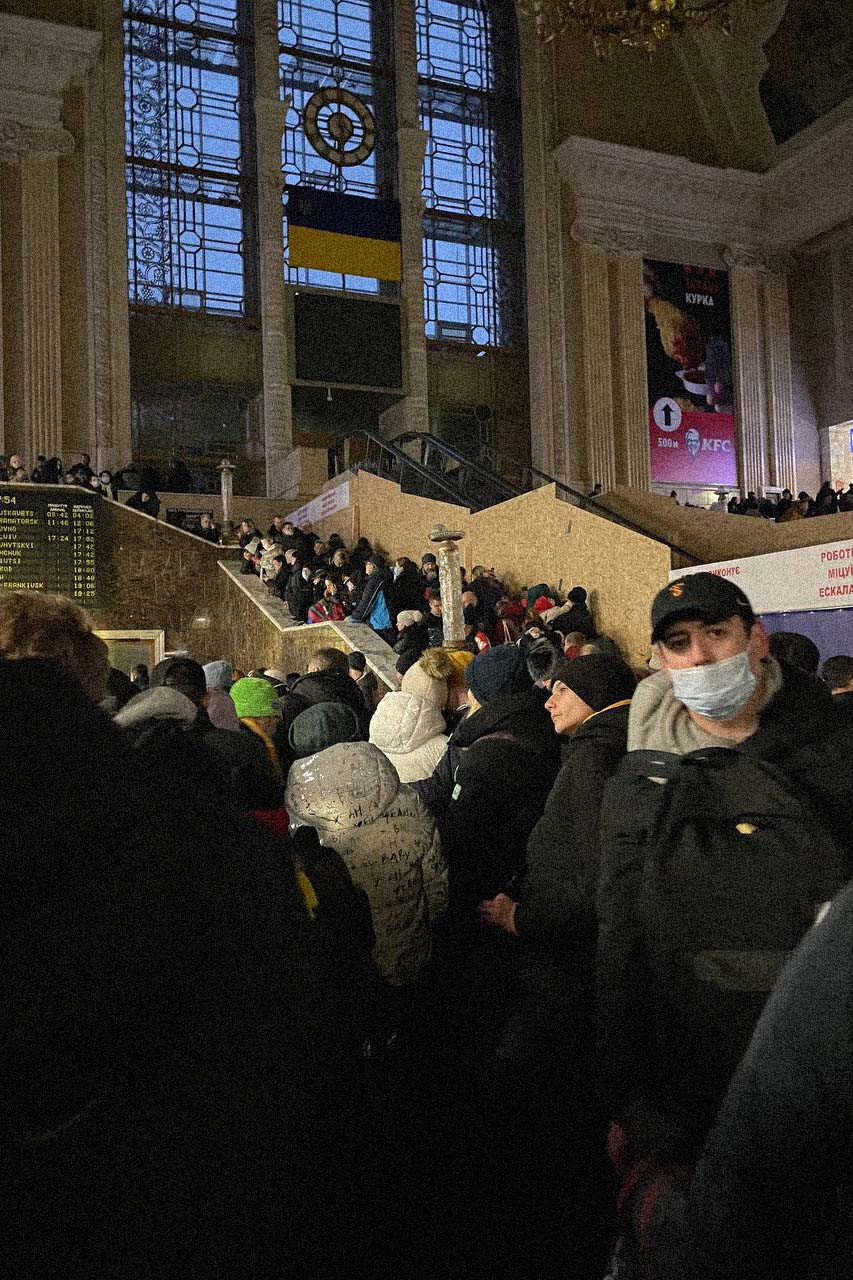

We arrived at the Kyiv railway station, having previously bought tickets for the Kyiv-Khmelnytskyi train, and saw all that commotion.

We arrived in Khmelnytskyi, and there the city was ready for war, there was enough stuff in the stores, and people didn't panic. My wife and I made a telegram channel for the Crimean audience about the world and Ukrainian news. It seemed to us that there was not enough information both about what was really happening in Crimea and about the war for the Crimeans.

We stayed in Khmelnytskyi until Easter. We kept talking with my wife that as soon as it became quiet, we would go back to the capital. But Klitschko said it was not a good idea at that time. So we decided for ourselves to see how things would go on Easter (yes, the Muslims decided to see how things would go on Easter). It did not get tougher, so we decided to go back.

When we left Kyiv, my friends told me, "Don't leave the house, you have a dark complexion, they'll take you away, beat you up or something." What? I immediately felt an internal resistance — I'm a Ukrainian.

I still keep an eye on things in Crimea and try to help both materially and informationally. I know that in Crimea right now there is a fear not only to say something but also to remain silent. Because right now for Russia this is also an indicator of support for Ukraine, especially for the local loyalists who monitor the situation from the inside. They even monitor local bloggers there, "You keep quiet? We'll come for you!"

When people see my Crimean registration, they sometimes ask, “What about the referendum, why couldn't you take up arms in 2014?” And by “you”, they mean the Crimean Tatars. They say, “You're Muslims, Allahu Akbar and all that.” But all that comes from ignorance, I take it calmly, I'm somewhat immune to it.

The only thing I hate — I don't know how to describe this feeling — is when they say that the war started in February 2022... We all need to realize that the war has been going on for eight years and it is the case for the whole country. But this is about a kind of ideal society — there probably isn't one yet. Maybe it exists somewhere, but I don't know where.

Recorded by Misha Pravilniy

Translated by Katsiaryna Khinevich