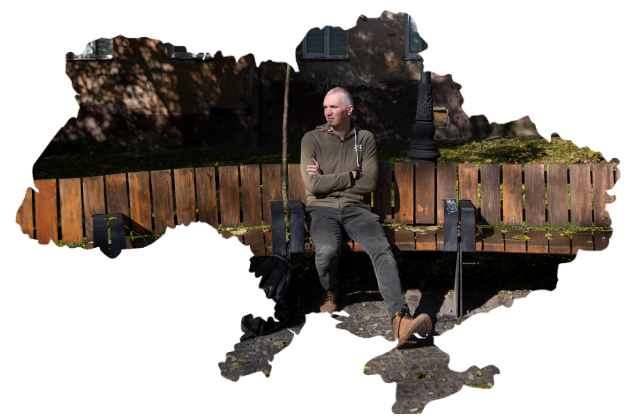

Anastasiia Glazunova and Anton Glazunov

Anastasiia — actress, teacher of acting, stage language and vocals at a theatrical studio

Anton — actor, lighting designer, set designer in theatre

Kharkiv — Izium — Zalyman village — Kharkiv

Nastia: Anton is from the Kharkiv region and I am from Kryvyi Rih. Five years ago we came to Kharkiv to study at Kharkiv National Kotlyarevsky University of Arts. We met there.

Anton: On the evening of February 23, I told Nastia to pack an emergency suitcase with all the documents just in case. I could feel the tension everywhere because we were expecting an attack. As for what happened before February 24, I have no memory at all. Only of that evening.

N.: On the morning of February 24, I woke up to our dog crawling on my pillow. Apparently, he heard the first explosions and got very scared. He's a nervous dog, he's afraid of loud noises.

A.: We decided it was dangerous to stay at our place with the dog and the cats — we have two of them. So we went to the subway.

N.: We didn’t have any doubts whether to take our pets or not, they are our family. We picked them up from the street and couldn't leave them to their fate again.

A.: We stayed in the subway for about half a day and then two more days in a basement bar, then decided to go to my parents in the village of Zalyman. It is 100 kilometres from Kharkiv, so the road was supposed to take an hour and a half or two hours. And it finally took 35 days.

A: On February 26, when we arrived at the station, we saw that on the scoreboard, one after another, the buses to Izium direction began to disappear: for seven thirty, eight, nine, twelve. We were travelling with our friend Andrii, he did not lose his head. He immediately found an old station wagon on BlaBlaCar. In it, apart from us, from Kharkiv went another guy and a girl with a chinchilla in a box.

You can get to Zalyman via Balakliia, or you can take the Rostov highway. We drove in the Balakliia direction and soon saw a huge column of Russian vehicles on the roadside: KamAZ trucks, gasoline trucks with excavators, Gvozdiki (self-propelled artillery units), TBr (tank brigade), and nearby — a large number of soldiers with machine guns.

N.: They warned us that shelling was about to start, so we went to the village of Volokhiv Yar (Chuguevsky district of Kharkiv region) to wait it out. There we found out that buses with children were going from Kharkiv to Kramatorsk, so we decided to follow them because civilians were not supposed to be shot at.

A.: When we went after these buses, an ambulance overtook us. Soon we saw the shelled bus, and next to it there were these under-soldiers and medics, who just stood there because nothing could be done.

On the way, we were warned that we would not make it to Balakliia because fighting had broken out there. A Russian army Tiger off-road vehicle approached us from another column heading for Volokhiv Yar — head-on into our car. It was only at the last moment that it moved to the side. This was their way of showing us their superiority, of intimidating us.

But when we approached the next checkpoint, we were met by completely different Russian soldiers — friendly, with ribbons of Saint George. They exclaimed "Hurrah!" but spoke with a sneer: "Oh, don't worry, we are our own people!" Those words made us feel not horror, but a great hatred for them.

N.: We reached the crossroads of Vesela and Izium. Only a little further and we would have turned right, where Anton's father was already waiting to pick us up. But a Russian tank blocked our way to Vesela.

A: The only road left for us was to Izium.

N.: Somehow we found a man who volunteered to be our guide. We followed him, followed by the buses with the children. Soon he stopped, approached us, and warned us that there was a hill ahead where a bus with civilians had recently been fired upon. So we had to drive at speed, with no headlights and with hazard lights.

We panicked, and pressed ourselves into the seats, I remembered the prayer "Great God, the only God, keep Ukraine safe for us" and quietly hummed it to myself. Anton kept turning around to see if I was crying. But I tried to hold on, I didn't want to worry him even more.

A.: We got to Izium on February 26 during curfew. Instead of two hours, it took us eight that day. In the city itself we were met by police officers, who addressed us in Ukrainian.

N.: Later we joked that we had never been so happy to see policemen, because it meant that the city was ours for now. Unfortunately, even then there were only police and a small number of TRO men to guard Izium.

A.: We went straight to Andrii's house. He was coming with us from Kharkiv. His mother lived in Izium, and she welcomed us very heartily that evening.

N.: But as soon as we sat down to have dinner, and exhaled a little, the first explosions broke out in Izium. And so we got stuck there for 35 days.

A.: During the first days, we stayed in the basement, going outside from time to time to see what was going on.

N.: First, the heating was cut off and it already got scary, because it was very cold at the beginning of March. We were keeping ourselves warm the best we could, sleeping all together, wrapped in blankets, with our cats on top of us and the dog laying at our feet. Then the gas and water disappeared. And on March 4, the electricity and phone service were gone as well.

We were joined in the basement by a five-year-old girl, a teenage boy, and elderly grandmothers. All together we listened to the walls shudder from the fighters firing shells at us.

A.: We started considering what to do next. While looking for cigarettes, we found out about the owner of a store from Vepritsky khutor, where they sold off-licensed cigarettes. In addition, Andrii had recalled an acquaintance who had left his house in the same khutor, with several dogs in it. It was not close, so we decided to cycle. So we started going to Vepritsy khutor to take care of the dogs, buy cigarettes and deliver them around Izium. Back in those days, we were told that after the war we would have a monument built for the fact that we delivered cigarettes under shelling.

A.: On our expeditions with Andrii, we wondered about a friend who was in another area with no connection. We decided to go see him. It was the middle of March. That day we saw everything the Russians had done: a burnt-out school, smashed and battered stores, half-destroyed houses with "children" written on them, two entrances to a five-story building levelled to the ground, where 44 bodies were later found under the rubble. We saw corpses lying in the street, a broken pedestrian bridge repaired with some kind of iron beds.

When we cautiously crossed that bridge and walked down Zamostenska Street, the first thing that caught our eye was a burned tank that crashed right into a house. And nothing was happening, there was dead silence. Andrii and I were walking through this terrible silence and all I could think about was that there could be snipers sitting around there somewhere.

N.: During those 35 days we were able to wash only once. My acquaintances had a house with a stove, and while we were washing, they started shelling the city again. By the time we made it home, we were already so sweaty that we would need to wash again. That was the first time I saw that ruined five-story building, with dozens of people killed in its basement, and many more such structures. It's horrifying to look at.

A.: The longer we lived in Izium, the more ordinary everything that was going on around us became. Every day we biked up to 20 kilometres, that's about 10-15 checkpoints where we had to show our documents. Sometimes we had to undress. The Russian soldiers were trying their hardest, as they liked to say, to "taunt" us.

N.: Anton has an owl tattoo. At one of the checkpoints, Russian occupants asked him what it meant.

A.: It was the end of March, still quite cold. I took off all my clothes. They looked at it and asked me what kind of owl it was. I answered that I didn't know because I had it made when I was 18. Then one said to the other, "Sergeant Major, we must check it, maybe it's a reconnaissance.” I looked him straight in the eye and said, "So check it, but can I get dressed?" He saw that I had no hesitation, let me get dressed and let me go.

N.: Then Andrii's mother said that the owl is indeed a symbol of Ukrainian intelligence.

A.: On March 26, Russian troops took full control of Izium, to that day they were not present in our half of the city yet.

N.: That day at 7 a.m. Andrii's mother woke us up, saying that there was a tank in our yard. We went out, and the tank's gun was pointed at us. There was also a kindergarten across the yard from our house — so they drove that tank over the fence of the kindergarten, straight ahead, destroying everything. The soldiers followed the tank, then some more vehicles.

A.: On March 29, we met my fellow villager Serhii. He said that he was going to walk home with his family to our village of Zalyman. The next day I called my aunt and she told me that Serhii was home with his wife and child. Two days later we set off on our way home

N.: We left Izium for Anton's parents on April 2. It was the only warm day when I finally took off my jacket. I had a backpack and a bag, Anton had a backpack, a dog on a leash, and two cats in one carrier.

A.: We exited through Peski, on the road at the turnoff to the Rostov highway we were stopped by a KamAZ, and the driver called me over to him. I walked up, and he took out three cans of meat and gave them to me. I immediately gave two to Andrii, who was seeing us off. From there we passed several checkpoints without any problems.

N.: Zalyman, Anton's village, was occupied from February 27 to April 1. The bridge to it was twice blown up by the Rascists, so we got to the river, and from there Anton's father and a fellow villager ferried us across in an inflatable boat.

When I saw Anton's parents, the tears flowed like a river, they wouldn't stop. We still looked so scruffy, covered in soot, my jacket was burned through, and Anton’s hair was very overgrown. That's how we entered their house.

A.: On May 12 we left for Kharkiv because my parents told us not to stay in the village any longer.

N.: The next day, when we returned to Kharkiv, we started volunteering at the charity organization Volonterska, packing and delivering humanitarian aid. Subsequently, we went to my parents in Kryvyi Rih, where Anton got his driver's license and we got married.

Now we live in our one-room apartment in Kharkiv: we hide from shelling during the day and sit in the hallway at night during sirens. Anton's parents live with us, as does a boy they brought from their village at the request of their friends.

I also work with children a little, giving lectures about theatre and puppets. Anton makes videos about stage movement for children. Little by little, we are getting used to what is going on.

Recorded by Alyona Vorobiova

Translated by Katsiaryna Khinevich

Photographer by Oleksandr Osipov