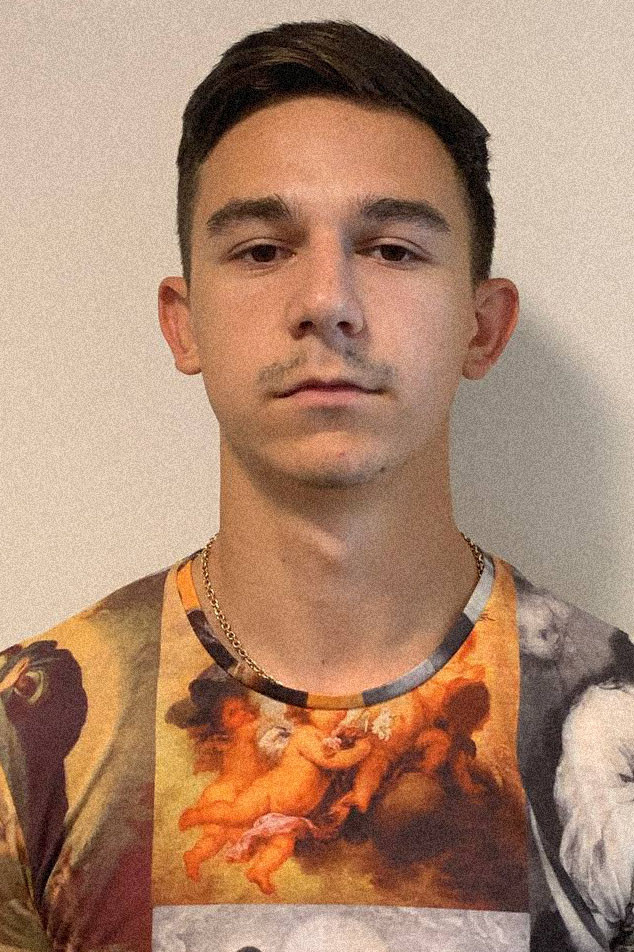

Rodion Khrystov

Volunteer helping IDPs and Roma children

Kharkiv — Uzhhorod

I am a Kharkiv native, and I was in my hometown when the rumors about the war began to spread, a few weeks before the full-scale invasion. Everyone was wondering if the war was to start anytime soon. And I thought to myself "What kind of nonsense is that? A war in 2022? With the country in which everyone second person living here has relatives?" I understood that there were battles in the Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts, but I never would have thought it could happen all across Ukraine.

On the night of February 23, I decided to watch the news on YouTube, even though I didn't care much about politics or anything related to it before. After watching the news, I started to get seriously worried and even had a sense that something was going to happen... But I didn't pay attention to it and went to sleep. Two hours later, around 4:30 a.m. a girl called me and told me that a war had begun.

I didn't understand anything, but I woke up and started waking up my whole family. My mother and father, who are in their 60s, my brother, his wife and their one-year-old baby, my sister, her husband and their four kids. My other brother, his wife and three kids. Two brothers, one sister. And five more children of my sister's, who are in the care of my mom (my sister died in a car accident). Yes, we live as a big family: we are Roma and can't do without each other.

Then we packed our bags, called our relatives in Ukraine, and finally realized that the war was real and it had started. We went out into the yard, and we heard the bombing. We could see something burning from afar and drones flying by. The scale of fear I felt was incredible, especially when I saw little children crying.

At about 7 or 8 a.m. we went to our relatives to figure out together what to do next. We drove out in our cars. The city was a huge chaos, with incredibly heavy traffic and nowhere to fill up. We got to the relatives' place, talked to them and decided to stay in Kharkiv because it was dangerous to go anywhere. They said that even on the road one might get beaten up.

We stayed at our relatives' for about a week, and we realized that it was getting harder and harder with every night — the shelling was very heavy. We hid in the basement of a private house. It all felt extremely dangerous, and we had problems with the food supply. There was nowhere to buy it in the private sector.

On March 1, we tried to take a train to the Kharkiv railway station (going by car was too dangerous), but we waited for three hours, and it turned out that the train only runs in the morning. On March 2, we left at six in the morning and arrived at the station, where there was a free train. Lots and lots of people, everyone in shock...

At the time we were to get into the carriage, two rockets hit some 500 meters away from the station. There were huge explosions, and everyone fell to the ground, about 1,000 people. Panic, children crying, people looking for their children. You can't put this dread into words, you need to experience it to understand how terrifying it was.

At first, they didn't want to let us on the train. I guess it was because we were Roma, or because there were too many men among us. But somehow God opened the door for us and we got on. Most of us didn't find any vacant seats, so we had to stand for about 20 hours. It was impossible to even sit down on the floor because of how many people there were.

We rode for more than 24 hours without any light. When we reached Lviv, we begged and cried to be let into the vestibule of the Lviv-Uzhhorod train. It was still cold outside back then, so we sat the whole ride in the cold vestibule.

The narrative that all gypsies are the same has always disturbed me. Every time I hear it, I try to challenge this idea and show by example that it's not true. Imagine that you know that your children may die, when you realize that your life hangs in the balance and you run from a war, from something you don't deserve at all... you are running to save your family, and at that very moment a rocket hits, everyone starts crying, you watch your children and nephews crying and looking for you to hold them in the hope you will save them.

And then you ask a policeman for permission to get on a train, and they tell you, "No!" they shout at you, "Go away! You're not getting on until everyone else gets on!" And something happens inside you and makes you think, "Why? What do we have to do with all of that? What have we done?" And you understand that it doesn't make any sense. But we were strong and somehow we got through it.

When we finally arrived in Uzhhorod, we ran into some wonderful people whose hearts were truly open. They gave us a house and helped us with the food supply. They really gave us a helping hand when we needed it so much.

Our Holy Trinity Church also relocated to Uzhhorod along with our relatives and friends. When we met our pastor, he first wanted to take us to the schools where the local government had set up shelters. But then the pastor of the local church, also a Roma, called us and said that there were several homes in the Roma camp that they could provide. That news cheered us up.

We arrived at the Roma camp, which felt very new to us because we had never lived like this. But at that point, we understood perfectly well that any roof over our heads is the glory of God and it doesn't matter what the conditions are, the most important thing is that we are alive.

Later, when we came to our senses a little bit, my friend and I started thinking about how we could become even more of a help here. I already volunteered, but it didn't take up all my time.

That was when a very interesting story happened. My friend Igor, who lived in a nearby Roma camp, was passing by a garbage can on his way home. He saw three young children there, dirty and unkempt, who were looking for something. He asked them what they were doing there. The children were frightened. They got down on their knees and started crying, saying they were looking for toys. Igor was really struck by this encounter. He went home and told his little sister about it. And she gave him her toys and he took them to the children.

That's when we came up with the idea of doing a summer camp for local and displaced children in need of support and rehabilitation. A five-day camp with meals and different activities for children from 6 to 14 years old. Now we are implementing this idea and we are waiting for grant money.

Right now I am having a hard time: my elderly parents, all the children and my older brother have already moved to another house, while my other brother and sister also live separately. Now I am the only one left, who has to feed his family while having no job…

In Uzhhorod, they treat us normally, because we act normally. But there are Roma who behave badly and disrespectfully, who make trouble, use illegal substances, etc. When someone does something bad, unfortunately, it becomes absolutely everyone's fault, because, as they say, "Why did you come here?" Speaking of discrimination, it does happen here.

There were also times when I started speaking in Russian and I what heard in response was: "Why did you come here? You'd better die there in Kharkiv!" It is kind of wild. If it wasn't for Kharkiv, who knows what would have happened in Uzhhorod…

I decided for myself that I would learn Ukrainian. I have a great desire to communicate in my native language. Now I am studying, trying to catch up with what I've lost. But it is harder for my parents, and I would like Ukrainian society to have more understanding of it.

I hope that the war will make people realize that we are one nation. It should help us get rid of stereotypes. When the tank story was actively spreading [at the beginning of the war there was a story on the Internet about a russian tank being stolen by the Roma] people reached out to us and said, "Well done! Could you steal a person for us?"

It's fun, and it's cool, and you realize that people somehow start to automatically treat you with kindness, instead of going just oh, gypsies! Those who understand what's going on in the country, don't care whether you're a Roma or someone else.

Yes, we are Roma. But the passport speaks for itself. Why am I not a Ukrainian, if I was born in Kharkiv? If I lived and studied in Kharkiv, I know the laws, I love my city, and I live by it. I want to help my country, I represent the same people as all Ukrainians, I've also experienced the same stress, people I know and care for with all my heart are dying too.

Unfortunately, people don't understand this and think we don't care. Like, "You're nomadic — you'll go to another country." But there are Roma who want to help their country so that we win and feel free. Because Ukraine deserves freedom.

Recorded by Misha Pravilniy

Translated by Volha Mikhnovich

Photos — personal archives of Rodion Khrystov and Hanna Sokolova, Graty