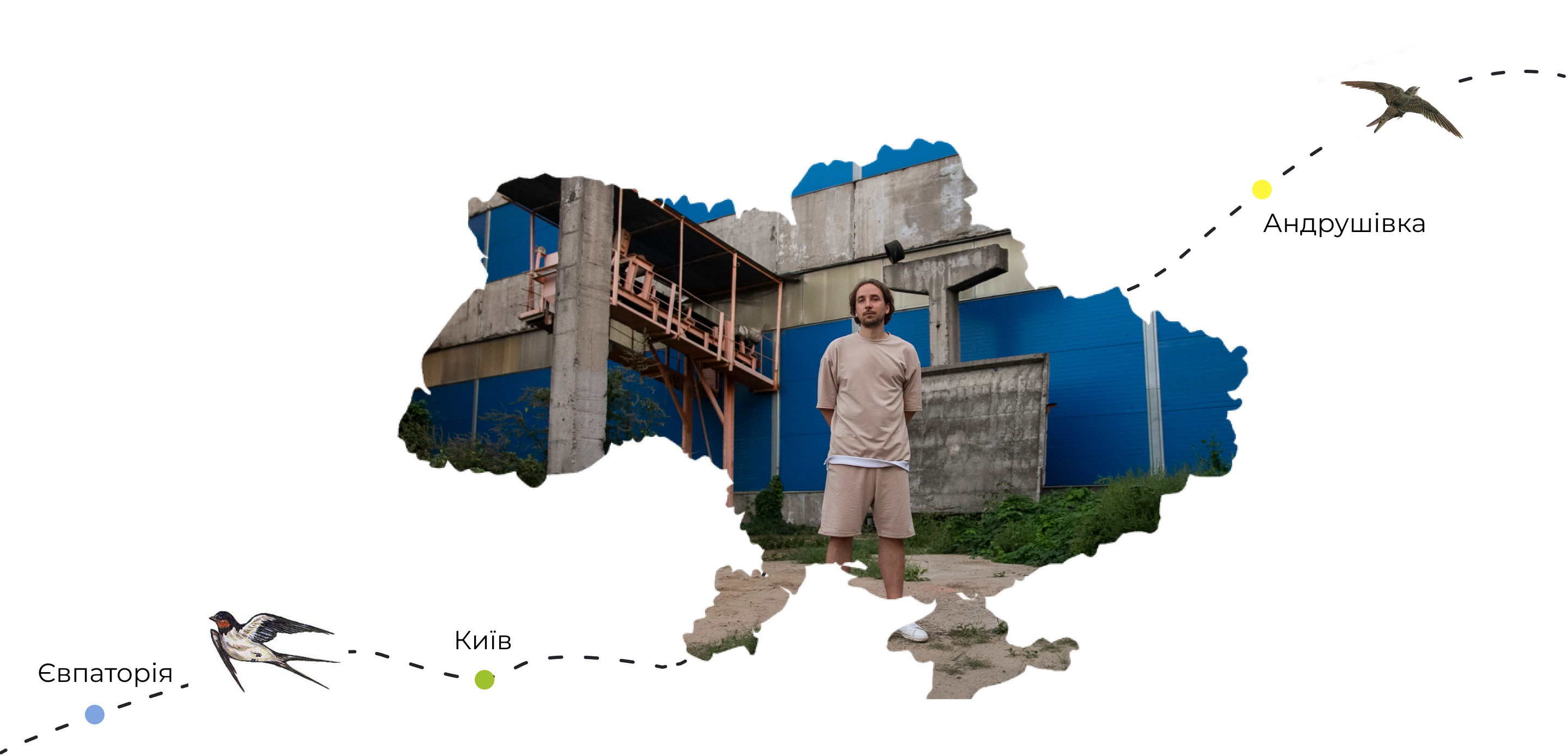

Roman Liakh

Public speaking coach

Yevpatoriia — Kyiv — Andrushivka (Zhytomyr Oblast)

I was born and raised in Crimea, spent 18 years there, and always considered myself a Ukrainian. Not the kind who rips his shirt on his chest and is a patriot to the core. But I understood that I was Ukrainian, and it felt as natural as breathing. Without any buts.

The annexation of Crimea was a complicated personal situation for me. By that time I had already been living in Kyiv for nine years because in 2005 I entered a drama school. I registered in the dormitory and was already a Kyivan according to my documents. My roots were only on the first page of my passport, "City of Birth — Yevpatoriia."

And you think, "Who do you think you are? You are registered in Kyiv, so live in your Kyiv!" It's like they took away what had always been mine and said, "That's it, you have no rights, keep out of it.” But I cannot just distance myself from Crimea: it is my birthplace, a part of my childhood, and of my life.

My mother, sister, and best friend remained in Crimea. Acquaintances told me how during the Maidan they were afraid that Bandera trains would come to carve them up. And they were relieved when the Russian troops came in. What a cheer there was... As if they had been pretending all their lives, and then suddenly took off their masks, "And we really have been expecting this to happen!”. And I just couldn't understand how that was possible.

Since 2014, I've been to Crimea four or five times, I took my children to Yevpatoriia to meet their grandmother and their cousins. I went for childhood memories and to visit my mother. We went, for example, to the seafront, walked along Duvanovskaya Street, past our theatre. I tried to keep that light inside, to keep it the way I remember it. But I came to my hometown and couldn't feel like a local.

It makes me cringe when people are saying things like, “Next year we’ll be making barbecue in Crimea.” I understand that the people who say these things are most likely not Crimeans. That is, they don't know the situation or the mood. For me, the return of Crimea is a mission without a solution. For every day the distance between people is increasing, and with the acute phase of the war just at breakneck speed. And it seems that people in Crimea are increasingly germinated with Russian thoughts, air, and narratives.

In 2022, when the active phase of the war began, my particular pain was that my mother, mother-in-law, and friends from Crimea, when talking to me, seemed to use a single page of the book, "Only military objects are bombed, civilians are not affected, don't go anywhere, it will soon be over.” I heard the same thing from different people, word for word.

On the night of February 24, I was asleep. There's a construction site across from our house. And at about 5:45 in the morning I woke up to the thought that a Kamaz truck had arrived, unloading something and banging its board like this — “Bang! Bang! Bang!” We had already had a history of construction workers starting work early, we complained about them, so this association was triggered in my sleep.

My neighbour immediately called me on the phone, "Roma, what have you decided?” I answered, "Wait, what is going on?" And she said, "Don't you know?" I logged on to Facebook and realized — the war had started.

I woke up my wife, the kids were asleep. A neighbour was on her way to the Zhytomyr region with her daughter and offered to take our children. We talked it over with my wife and agreed. And we stayed on our phones for twenty-four hours trying to figure out what was going on.

My stress response is to "freeze" and I was completely confused. And so as not to go completely through the roof, I went out for a run. With a flag. It came out to 24 or 26 kilometres, almost symbolic of the start date. I was just jogging along the traffic arteries, there was a huge traffic jam on the way out of Kyiv, and I had the flag on my back. A lot of people were honking at me, shouting something invigorating. I felt how... I don't know how to say it not to be pathetic... How much I needed that at the moment. I wanted to feel that we were together.

The next day I said, "I don't want to be separated from my children.” We went to a friend's house in the village. We picked up the children and moved to Andrushivka, Zhytomyr region, to my friend's house. His relatives had already gathered at his place, and we also brought our friend from Kyiv.

On February 27, we decided that we would take the women and children abroad. I got in my car and took three women, four children, and all their things. And I didn't have a very big car, it was a miracle they could fit in. We drove to the border with Moldova, that was Mogilev-Podolsky on the Ukrainian side, so that they could go to Istanbul. That was the last place I could get to. I drove my family to the first border crossing with all their suitcases, said goodbye, and watched them cross that bridge to the other side. And drove back.

A few days later, my friend's parents left, and my friend and I were left alone in the village. We sat there for two or three days and realized that we could just go crazy from just sitting doing nothing in this crap situation. Each of us had a car, and we started carpooling and volunteering. We even asked around among friends to set up a small financial fund for gasoline. We had volunteered for almost three months until the gasoline collapse, with about 30,000 kilometres between the two of us.

I first came to Kyiv on March 23, for a day, and I walked around, reminiscing. I went into the children's room, found the little dog from the cartoon "Open Season" called Weenie, and took it to my car. I also took a little drawing by my son where he had drawn himself and his brother.

No Zoom or Vibers calls can replace live communication, being around, talking about everything that's going on. I feel like I'm losing touch with my kids. The older one turned eight, the younger one is five, and it's such an age... I don't think there's any age when a father is unimportant. And I feel that my children need me.

I miss them very much. I hope we will have a chance to meet in the near future. But since the Russians keep launching missile attacks, we are not considering returning the children to Ukraine right now. And as for me going abroad... There were acquaintances who left in exchange for money, illegally. I am not considering such an option at all, because I don't want to go one way. I want to be able to return home.

Recorded by Olha Vasina

Translated by Katsiaryna Khinevich

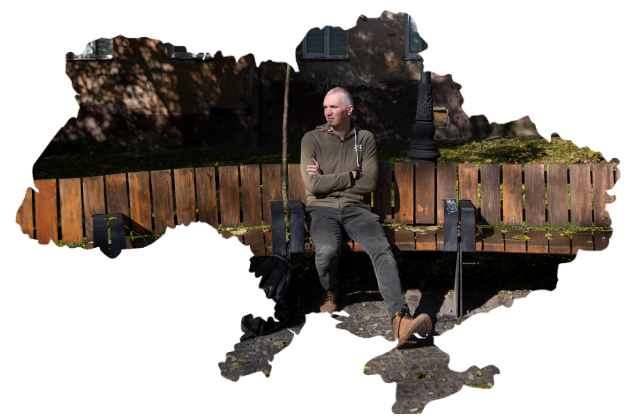

Photographed by Vladislav Yevdokymov