Unde enim eius est dolorem sed aut. Est asperiores nam rerum delectus ad occaecati. Rerum voluptatem sed reiciendis alias. Earum soluta possimus nam provident. Optio eaque est magni et est fuga quibusdam. Ipsum perspiciatis a in.

Kyiv — Petrushky — Khmelnytskyi — Kyiv

The night before February 24, all my family, including my eight-months-pregnant wife and my son, knew in our hearts that something was going to happen. We'd already packed a small suitcase and decided that if a full-scale war broke out, we would go out of town. Until then, we decided to get a good night's sleep. My wife and son went to bed, while I stayed up all night: I waited.

At four in the morning, I heard the first explosions. Our building turned into an anthill: all the neighbours woke up and started moving around. I looked out of the window and saw people running around with pillows and bags, packing everything up. As a matter of principle, I didn't wake the family up, because I realized that they had fallen asleep at around 2 a.m. and no one knew when they would get some sleep again. My wife woke up around 8 a.m. and I said to her: "Darling, stay calm. The war has started." She still remembers that phrase.

I got my son up, we packed up the pets - two cats and a dog - took some bags and food from the fridge, got in the car, and left at 10 a.m. We thought that the traffic would be more or less clear by then, but it was not. The usual drive to our country house in the village of Petrushky outside Kyiv takes about 30 minutes, but we were on the road for six and a half hours, and it was already dark when we arrived.

In Petrushky we realized that we didn't have enough food, so we decided to go to a grocery store in the morning. We woke up and went there all together: a woman with a giant belly, me, a kid, and the dog. As we were leaving, we saw helicopters with Russian paratroopers heading towards Hostomel. They were flying literally above the ground, at a height of 50 metres maximum, right above us. When we were passing the lake, the Russians landed troops in Hostomel, and the AFU started firing at them. The troops were retreating, and we kept walking.

We got to the centre of the village. The street battles began, and everything around us was in smoke and exploding. But the sense of hunger prevailed and we didn't stop.

We walked into the grocery store and there was nothing there - the shelves were almost empty. We bought one ice cream, some biscuits, and a detergent. We returned home to the sound of shelling.

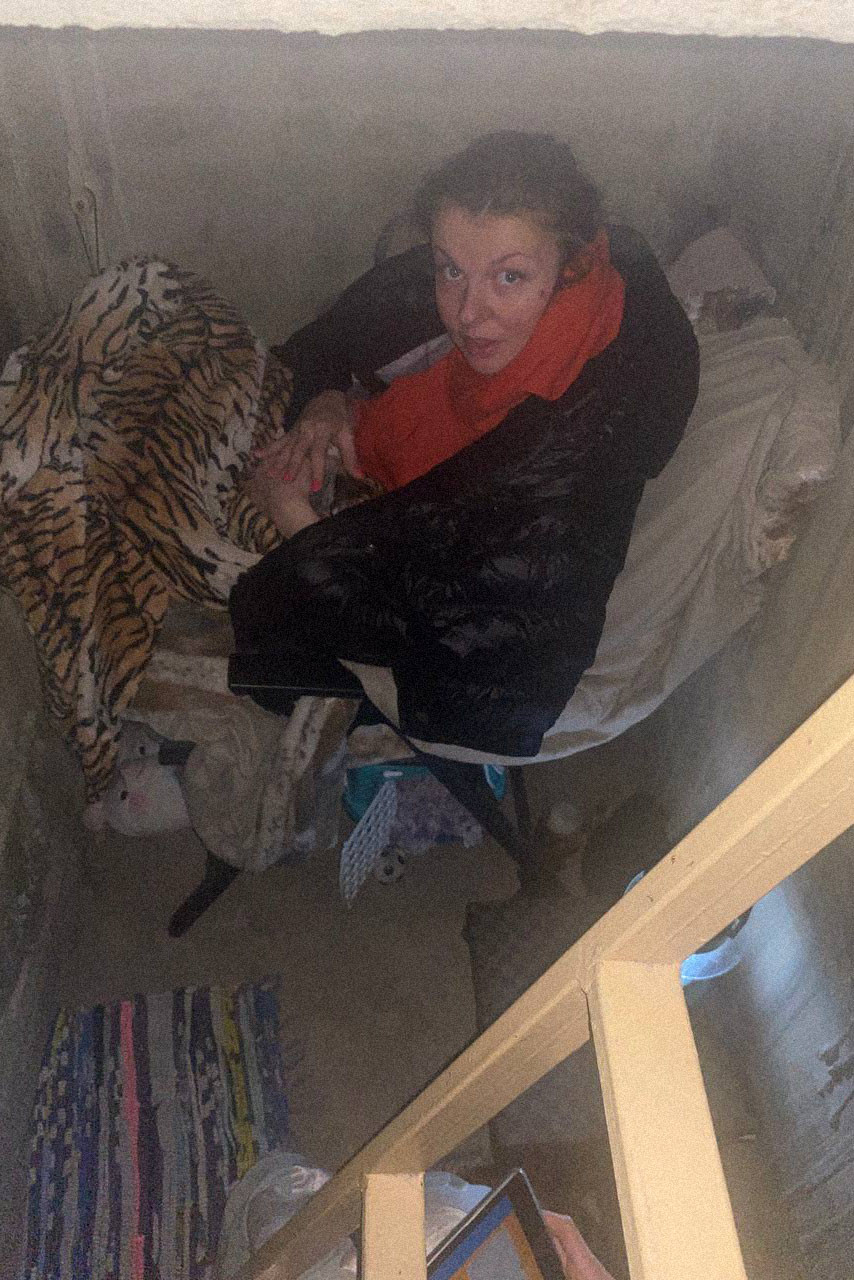

On the third night, we woke up to the sound of rockets exploding nearby. We crawled into the basement and didn't come out from there for the next three weeks. There was another reason to panic: it was about -12°C outside, and the house was designed only for the summer. There were no radiators, only underfloor heating, and air-conditioning. The communications got jammed, then the Russians bombed the regional electrical substation somewhere near Kyiv that supplied the village with electricity. There was no light for about a day and a half, and there was basically nothing to heat the house with. Fortunately, the substation was soon repaired and the electricity was back.

On the fourth day, when the circular defense of Kyiv and the region began, the AFU placed howitzers or other systems somewhere near us. It was clear that artillery was working: they were firing around the clock, most of all at night.

On the fifth day, my son yelled: "Look out the window!". So I look out and see two enemy helicopters flying by. One of them gets shot down, followed by the second. They fall not far from us, near the lake.

My wife was eight months pregnant, so we had to do something. We knew we might need a caesarean, and surely that was an unreal thing to get in Petrushky. Besides, we could go into premature labour any day.

In addition to that, we didn't know if Russian troops would enter the village or not. Every night we turned the lights off, and I stayed awake on watch worrying about a possible occupation.

I still had a gas pistol from the 1990s. However, I realized that it might only come in handy as protection against looters. Once you have trained military men sent to seize Kyiv in your house, and you pull out this peashooter, they are likely to shove it where they want it to go. If you pull out a gun, use it, otherwise, you will only cause more aggression. So I knew that the pistol wasn't going to help me.

The second week, I reached out to an acquaintance of mine and in the course of the conversation told him that we needed to leave. He asked me to wait, then called back and put me in touch with the military who were evacuating people from that area. A man called us on the phone and said: "You have 15 minutes. Pack up."

We grabbed everything we had at hand and ran outside. My wife then said: "It's not what you've saved up that matters, it's what you can take with you." The shelling wouldn't stop: when I went outside, my ears popped. The temperature was -8°C... The military guy called me again to ask where to pick us up, and then the shooting started on the other end of the line. I could hear him swearing, and the connection went off…

We realized in despair that we were not going anywhere. But a few minutes later the guy called again. He said their car had been shot at and fortunately everyone survived. They couldn't come to pick us up, but they could meet us in the direction of Horenychi, five kilometres away from our place.

We got in the car and drove off. We opened the windows so that everyone could see that we were civilians and didn't shoot at us. We were driving in a so-called 'grey zone' through the forest and orchards. It was unclear who was an insider, who was an outsider, or who was shooting. Everything around was on fire. At that time Russian troops were already standing near both Petrushky and Horenychi. There was only one green corridor left, which we managed to reach.

It was the fastest trip of my life, it felt like I teleported from point A to point B. That was where we were met.

The military escorted us to Kyiv. I tried to thank them, but they refused the money. We went to a shop where there was almost nothing: we took some nonsense like an Israeli kosher roll, a very expensive tea, and something dietary and lactose-free. We got home and started eating before even taking off our coats. We were so happy about this meal.

The labour might have started at any moment, and Kyiv was still an unsafe place. Our relatives from Khmelnytskyi invited us to stay with them. We went to the railway station to figure out a way to leave. There were no timetables, only a train that was about to leave. We ran home, packed our stuff again, and returned to the station. The train attendants wouldn't let me in, saying only women and children were going. I said: "My wife is eight months pregnant! How can you imagine me staying?"

At last, I was allowed onto the train and at 9 p.m. we reached Khmelnytskyi. Not a single lantern was lit at the station, sirens were wailing, and everything felt very unsettling.

But we were welcomed by our relatives and the next morning we realized that Khmelnytskyi was safer than Kyiv, there was food in the shops and everything seemed quite fine.

However, the anxiety wouldn't leave us and we returned to Kyiv a week later. My wife's pregnancy was a factor in this decision. As it turned out, no clinic in Khmelnytskyi was likely to be able to provide the operation. The thing was, my wife's umbilical cord was wrapped around the baby's neck twice, while local clinics were so old they were falling apart. So, the operation might have taken place in the waiting room, in the basement or in the corridor.

Anyway, delivery is a whole other story. Let's just say that everything ended well. Now we have Eva Aleksandrovna, we are in Kyiv, and I have switched from selling civilian goods to supplying the army with everything they need.

Recorded by Misha Pravilniy

Translated by Volha Mikhnovich