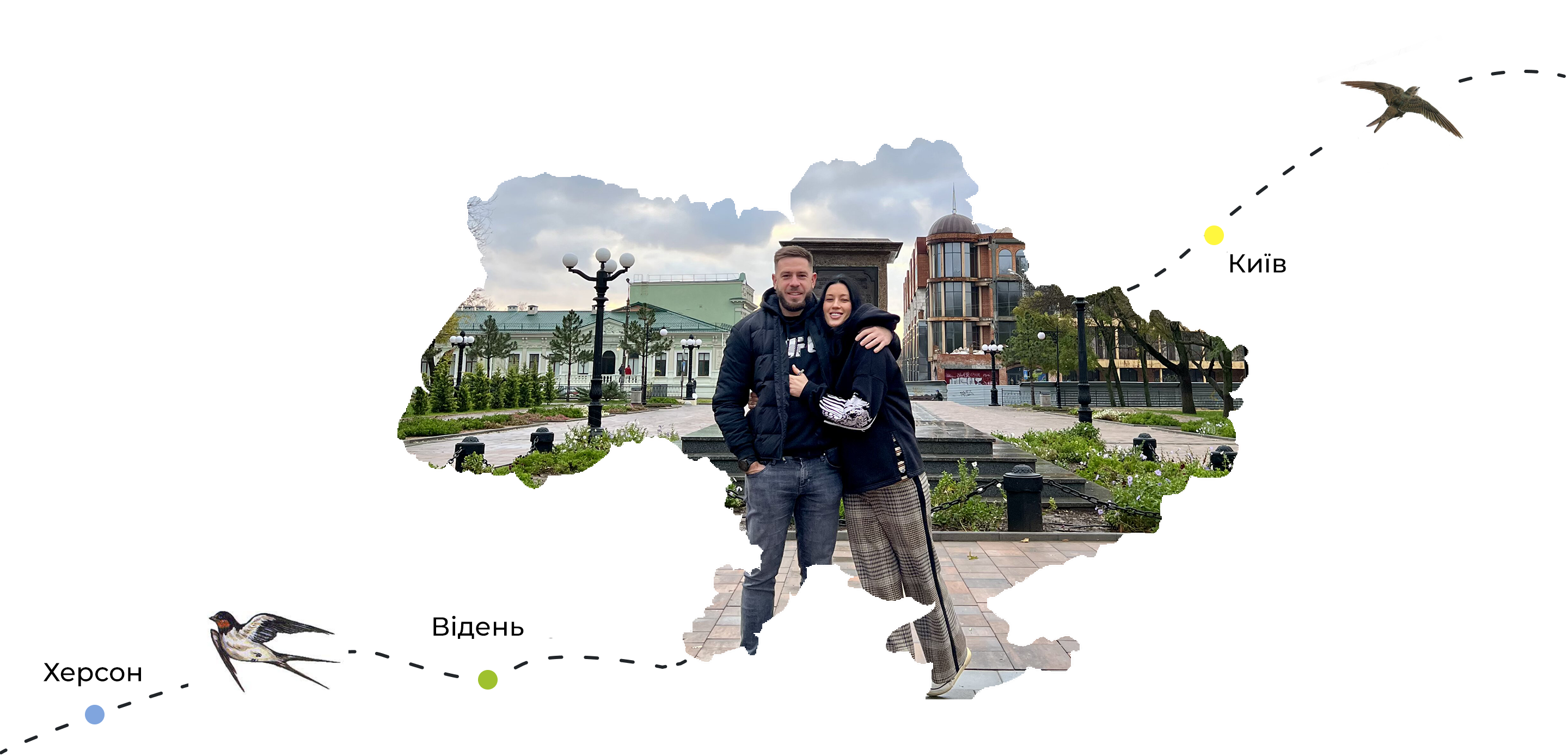

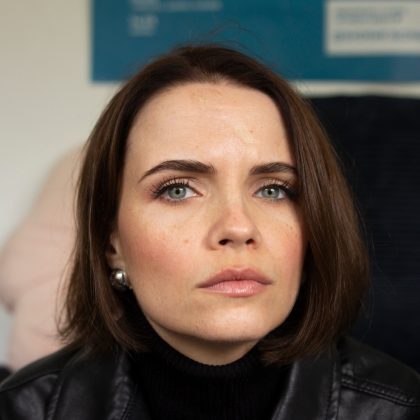

Oleksandra Knyha

Costume designer

Kherson — Vienna — Kyiv

We were in no way prepared for a full-scale invasion, as we didn't take the threat seriously. Friends wrote to me: "Maybe it is time to pack already". I would dismiss all suggestions of a kind, replying: "Can we not touch these topics, because I'm getting anxious. We must focus on the positive and think about the best".

On February 23, we went to the Mykola Kulish Theatre to see the premiere of "Eternity" by Serhiy Pavlyuk. That was such an extraordinary performance, perhaps the best one I had ever seen. After the performance, we went to a bar to hang out a bit and went home after that. At about 5:30 a.m. Yulia, a friend of mine, called me and said: "Sash, a war has started. Russia has attacked Ukraine."

My boyfriend and I were in shock. We started packing our suitcases, just throwing things in one by one without any plan. I told my children to pack their suitcases too. My son was 13 at the time, and my daughter was 14. Georgii agreed, but Margo said: "No, I'm not leaving Grandpa and Grandma, Dad and the dogs. I'm not going anywhere."

We stayed with friends for the first few days because they had a basement. Of course, we were constantly on our phones, monitoring the news and the Telegram channels. No one knew what to do, or how to act. Everyone bought food because shops started to close. Some people left the city, and some remained at home, hiding.

When the Russian troops entered Kherson, we were so terrified. It was like a horror movie, so surreal. But then clarity came: that was our reality. What we needed to do was to gather our thoughts and figure out how to act in order to save the lives of our loved ones, our children, and our own.

Everyone started getting text messages encouraging people to go to pro-Ukrainian demonstrations, and to my surprise, a lot of people showed up. I was also at the demonstration on March 5. Anechka, a friend, had given me a vision board as a New Year gift, and I was supposed to stick pictures of all the things I wanted on it. But I never did it, because I couldn't figure out what I wanted. So I used that board to make a poster: I wrote "Kherson is Ukraine" on the backside.

My boyfriend, Denis, and I went to the protest together, but at some point, we lost each other there. The connection went out, and it was really scary. There were snipers on the roof of the regional administration. There were military men everywhere, and they could start shooting or use teargas at any moment. I saw my theatre community and came up to them. They made a poster saying: "Russian warship, go fuck yourself" and many other posters about Putin. Then the crowd headed out to the Eternal Flame, and I went home because it was getting dark and I still had to find Denis. I guess it was God who led me away because at the Eternal Flame they started shooting civilians.

Then there were more protests, where the occupiers used weapons and gas. Even when I walked a block away from the place of a protest, tears would stream down my face and I would start coughing. That was how the protests of the Khersonians were cracked down.

In March, the Russian soldiers came to my friend's house to conduct a search. My father was a theatre director, and she was his deputy. The Russians were looking for her son because he was in the National Corps. They turned the whole place upside down, took all the money, took the computer, the phones, as they said, "for a clean-up". Those were my first close friends to be visited by the Russians.

A few days later, on March 23, they took my father with them. He lived in a private house in Oleshky [a town on the left bank of Dnipro, across the river from Kherson]. It was in the morning: they arrived with snipers, surrounded the house, and took everyone outside literally in their pyjamas. They turned everything upside down and took Dad away for interrogation. They said, 'Pack his things for a few days. If he behaves, we'll let him go."

The Russians wanted Dad to cooperate with them, and open the theatre under the Russian flag. They warned us not to make any statements on social media and said that everything would be fine as long as we kept quiet.

We didn't know what to do. My brother informed the Mayor of Oleshky that my father had been taken away, and the former made a statement about it. So the information about my father's kidnapping started to spread very fast. Georgian and Turkish theatre workers wrote an open letter to President Erdoğan of Turkey, and our friends started pushing the subject through the Verkhovna Rada. The story received maximum publicity.

I don't know what exactly helped, but in the evening Dad was released. Half an hour before curfew they dropped him off in a dark place, not in Oleshky, but in Kherson. Dad managed to find out where he was, walked to his acquaintances' place, spent the night there, and we met the next day.

Five days later they came to Dad again, this time to his workplace. The first time they had a conversation: Dad had his opinion and they had theirs about how they had come to "save" us and what they wanted in the first place. Of course, they didn't come to an agreement with Dad, because their positions were completely different. When they came the second time, they basically threatened the family. We have a huge family, and they knew everyone's name, how many grandchildren there were, how many children there were, and where they lived. They hinted that things could happen to them if he didn't cooperate.

After that, we decided that everyone had to leave: first of all the father, his family, and his brothers. They first moved from Oleshky to Kherson, to separate places, and then, when the corridor opened up, one by one, they left. And so did my children.

I stayed with my boyfriend waiting for liberation. In the beginning, we believed it would happen soon.

We volunteered, but we did it quietly. It was hard because all the volunteers collect money on social media. I didn't know how to arrange it. I couldn't write posts, so I only wrote a few times about raising money in stories, because they disappear after 24 hours. There was less chance of them tracking you down. The first ones to join the fundraising were my friends from abroad: Spain, Italy, America, Germany, Norway, and then - from all over Ukraine. I'm incredibly grateful to everyone who joined, it meant so much to us at the time.

We collected clothes, shoes, blankets, bedding, and food. Some of it we bought ourselves and the rest our friends donated to us. All this stuff was delivered to schools in the city centre, in the KhBK (a district of Kherson named after the Kherson Cotton Factory) and in the Tavrichesky micro district, where the displaced people from Stanislav, Bilozerk and other villages nearby were staying. Thanks to Denis's friends, we managed to help the orphanage in Stepanivka.

The hunt for volunteers started. One guy we worked with said, “Sash, they stopped me today when I was carrying food and my friend was beaten up.” Then he said, “They hit me in the ribs with a rifle butt today.” They also came to inspect my friends who were collecting aid in their café and buying groceries. Later my friends were summoned for questioning. One by one, the volunteers I cooperated with stopped engaging in that work or left.

Food was no longer brought in from Ukraine, so people started to adjust to the circumstances as best they could. The central point of events was the Dniprovsky market. It was as if we had been back in the 90s: you walked through the bazaar and saw cars with their boots up, selling cigarettes, sweets, everything at once, whoever was after what. There was milk in big tanks, vodka next to it, grannies selling vegetables. Then supermarkets and pharmacies with Russian products started to open.

In the summer, on the fourth month of the occupation, I was walking through the market and saw Ukrainian sweets being sold from a stall. I grabbed the sweets and with tears in my eyes said, "Girls, where did you get them?” And they said, "There was an illegal delivery." I said, "I'll get some.'" And it was such a treat to eat those “Romashka” and “Chervonyi Mak” candies because I hadn't seen them in a long time.

We first lost the mobile connection for a long period of time at the end of April — the beginning of May, for four or five days. Then everyone was scared because we were cut off from the whole world, we didn't know the news, what was happening to our relatives. Later the connection disappeared completely, but russian SIM cards were sold. People were afraid because in order to buy a card, they had to give their passport data.

I would not insert a Russian SIM card for a very long time, I had an internal protest. But when people couldn't find me for half a day, I finally said, "Okay, okay, I'll insert your SIM card." We didn't know for sure how our data was being monitored. We warned loved ones not to send us any provocative information for which we could get into trouble.

There were checkpoints in the city, where the russian military would check the phones. If they found the information they did not like, they would take the phone away, or they would beat people up or give the so-called educational "talks". People already knew that when they went out, they had to clean their phones, delete photos from demonstrations, delete Telegram news feeds, and sometimes even Instagram and Facebook.

And you also had to talk to the russians at the roadblocks. I remember I was driving on my own and a military officer says to me,

“Alexandra, give me your passport.”

He looks at the documents and says,

“Are you married?”

“Yes, I am.”

“And where is your husband?”

“He's working.”

“And what does he do?”

“Trucking.”

“You ship anything for the Armed Forces of Ukraine?”

“No. We just deliver groceries.”

“I see. Well, that's too bad.”

.

“What's bad?”

“It's bad that you're married.”

How was I supposed to respond to that? And then he didn't know what else to ask me, and he was like,

“Well, get out, open the boot.”

I mean, he still wanted to have a look at me.

We tried to dress very low-key, even when it was very hot and we wanted to wear shorts. I have a tattoo, so I carried a shirt with me all the time: when I drove through a roadblock, I would put it on, so they wouldn't ask me what kind of tattoo I had.

In July, when we were staying with friends on the island, they came to search us too. I remember that morning well because I woke up to gunshots: they had shot the cameras on the house overlooking the friends' yard.

Denis told me, "Stay upstairs, don't go out, so I don't get nervous." If they had taken him somewhere or taken him away, I would have been left alone in the house with them.

The russians went around the house: they were looking for weapons, and there was also a safe. They couldn't open it because we didn't know the password, so they wanted to blow it up to see what was in it. We dissuaded them because we knew that it could blow up half of the house. They checked all the rooms, and the whole yard, they asked why there were cameras, and who we were watching. They said goodbye and left. We were very badly shaken at the time.

Everyone they came to see, everyone they took for questioning, then left. And for us, their arrival was a significant contribution to the piggy bank of situations that made us finally say to ourselves, “That's it, we have to go.”

If it hadn't been for my partner, I wouldn't have made it through those five months. It's always scary for a girl to be in an occupation on her own. And thanks to his ingenuity we left safely. He told me, "Your mission was to protect Kherson, and mine was to protect you from everyone.”

We left Kherson in August. We had already had our suitcases packed, so one day we just got in the car and left. We didn't tell anyone, we didn't even warn our loved ones.

We travelled via Crimea and Krasnodar. Denis has long been involved in cargo transportation and logistics; he knows where to find the traffic capacity of checkpoints. We knew that at that time there was a very big traffic jam on the way out through Georgia. So we drove through Moscow.

We did not take off our number plates, we did not smear the Ukrainian flag. We were even sometimes let ahead in the Krasnodar region and that surprised us. We saw cars with Zs and St. George ribbons painted on them, but not many.

We drove through Moscow at night, with Den driving as fast as he could to get out of that area as quickly as possible. Around four in the morning, we stopped at a petrol station, rested for a few hours and drove on. We reached the Shumilkino checkpoint in the Pskov region, on the Estonian side of the border, where we were interrogated and our documents were taken away.

In Crimea we were also interrogated, Denis was held for almost four hours. They checked the phone, asked questions, and took him outside. They monitored his behaviour, then called him back and asked about the information they found on his phone.

We reached the kids in Vienna, and spent some time with them. Only when we were already in Austria did I tell my family that we had left. And then we went back to Ukraine, now we are working in Kyiv

When I first went to a Silpo supermarket in Kyiv, I started weeping. Tears were pouring down my face and my heart was crushing because I realised that people in Kherson didn't have that, that had been taken away from them. I came up to those Ukrainian goods, held them in my hands and looked at them. Of course, I filled a whole cart.

When I saw the news that the Armed Forces of Ukraine had entered Kherson, I couldn't believe it at first. Because it happened so unexpectedly fast, it was like a miracle. I cried a lot and jumped around the flat for a long time, and those emotions kept me going for a few more days. Then I started to worry about the left bank and what would happen there. There are rumours about Oleshky: first I hear that it has also been freed, then I hear that it hasn’t been freed yet. My heart aches for the left bank and the people there.

I managed to go to liberated Kherson for one day — on November 19. First, we went to Mykolaiv, spent the night there. It was a strange feeling because Mykolaiv used to be a frontline town. When it started to rain with a thunderstorm and then a siren sounded, my anxiety kicked in.

A sense of joy intermingled with sadness. On the way to Kherson, I was holding back tears because I saw destroyed villages, petrol stations, and roadside cafés. Once in the city, my heart felt warmer, but the city was empty, abandoned, and neglected, and houses were damaged. It made me want to wash everything thoroughly. But is it possible to wash away this trail of suffering from one's soul?

Recorded by Olha Vasina

Translated by Katsiaryna Khinevich