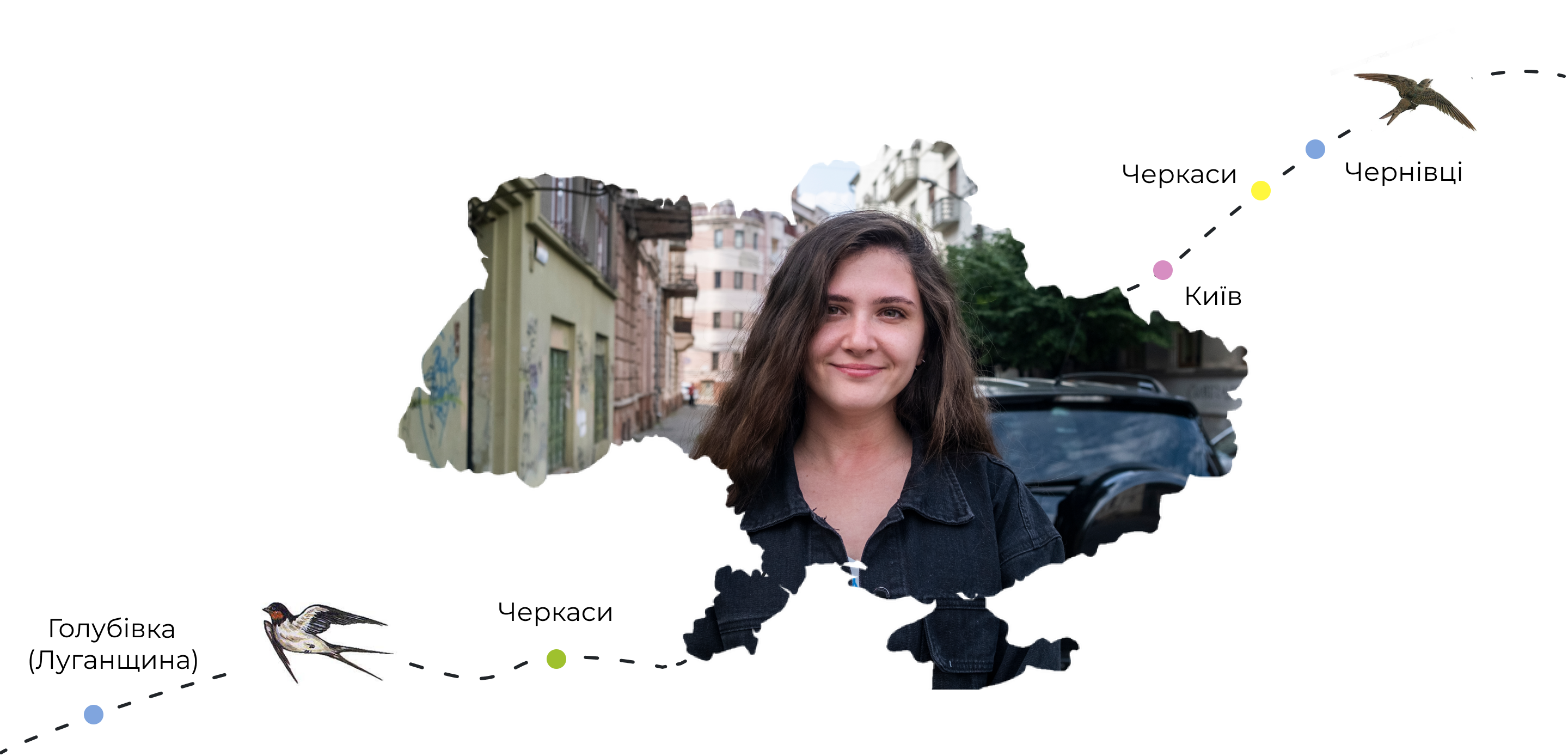

Maryna Klimchuk

Communication specialist

Holubivka (Luhansk Oblast) — Cherkasy — Kyiv — Cherkasy — Chernivtsi

The war first kicked me out of my home in Kirovsk (now Holubivka) in the Luhansk Oblast in 2014, when I was 16 years old.

I was in tenth grade, and my classmates and I were already dreaming of how we would dance the graduation waltz in a year, imagining how we would celebrate the day, and even making a playlist already. And then everything suddenly came to an end because of the war.

I remember a lesson in which our teacher told us that "The People's Republic of Luhansk" was to be declared on the day. I was in tears just at the thought of it. But so many people cheered. I couldn't figure out why.

Now, eight years later, the escalation of the war feels quite different. Back then, the countdown seemed very vague: it was unclear what was going on. But February 24th stamped itself deep in my mind.

The second time the war caught up with me was in Kyiv. I remember my cat aggressively trying to wake me up that morning. She pushed me to the side and behaved in a very odd way. But at that moment, I thought she was just trying to get some of her toys that I might have been sleeping on. And drowsy as I was, I just shooed her away. It was later that my friend tried to wake me up too. She said: "The war has begun." And I was like, "What the fuck? Again?"

I remember calling my mom same very moment and telling her that I didn't know what to do. Next, in this stress, I decided to wash my hair. I thought, "If not now, when will I be able to do it?" And that was my emotional response to what was going on.

My boyfriend lives in Cherkasy, so I immediately made a plan to leave Kyiv and go to him. I packed a small backpack, threw my swimsuit there for some reason, took my cat, and contacted my friends, who also decided to go to Cherkasy. Six of us were leaving the capital in a little Audi: I was sitting on my friend's lap, while my cat rode on top of me.

Cherkasy is a special city to me; it was where I found myself after being displaced in 2014. And then it happened for the second time. But these experiences felt very different because back then I had been on my way to the unknown, to a new city, to study and graduate from school with strangers. While the other time, I was on my way to a city that had already become a new home once, to a person I loved.

Eight years before, I had moved to Cherkasy on my own. Although my relatives hosted me there, it was not the best experience of my life, because they didn't support me. It only became a little easier after a year, when I went to study at university. Many of my classmates had also moved to a new city for the first time. All of them were from nearby towns or villages, and they were also starting all over again, just like me. I still missed my home, my family, my friends, though. I felt the worst at weekends when my classmates went home and I had no place to go.

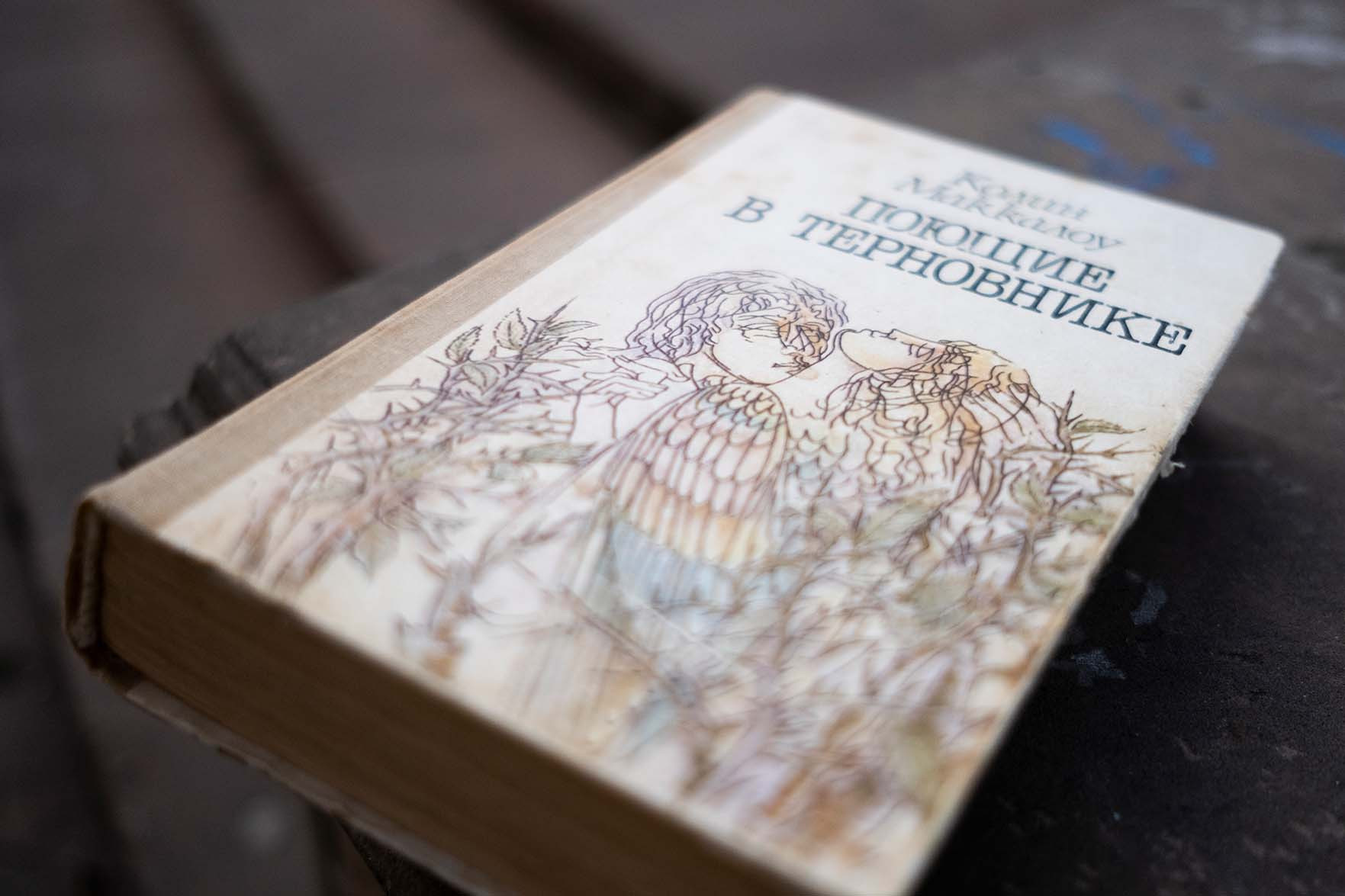

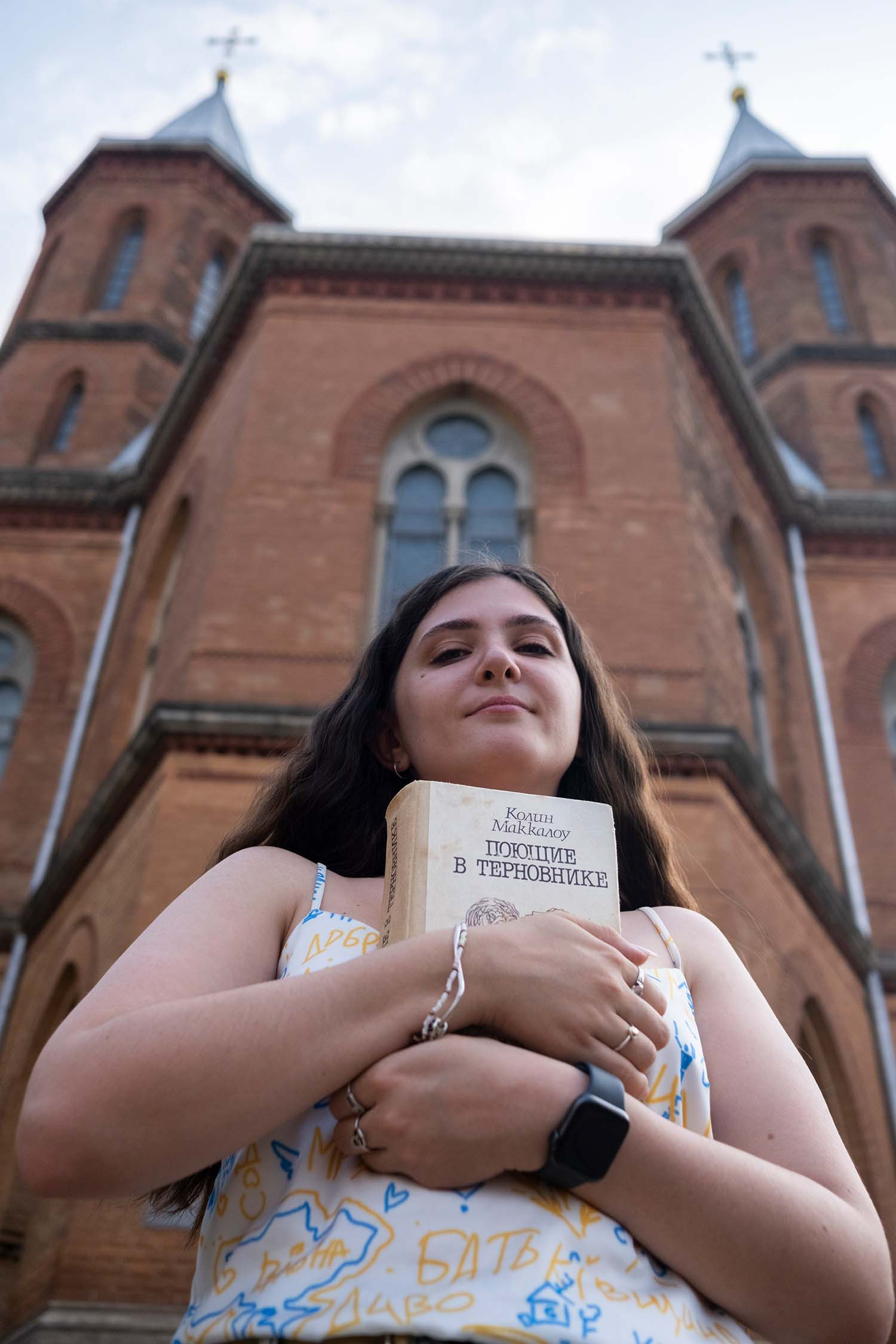

The only special thing I had with me was the book The Thorn Birds. I took it from my grandmother's library when I left Holubivka in 2014, and I still keep it as a memory of my homeland and family.

I was first able to visit the Luhansk region after a year and a half. It was then that I learned that the feeling of home had changed a lot. And the reason was people. I saw that many of those who had previously been around me got committed to the views completely opposite to mine, and became victims of Russian propaganda.

I remember running into my former teacher in Holubivka. She kept asking me how I was doing, how I was received in Cherkasy, and whether I was bullied because of the Russian language. I answered that I liked it there and that I was practicing speaking proper Ukrainian, and that I felt supported. And then she asked me if I had been to Lviv and if it was true that they ate children there. I think if someone else told me this story, I wouldn't believe it. But it happened to me, I heard this question from someone I knew, and I was totally shocked.

I could feel a huge gap between me and most people in my hometown. And at some point, I had to accept the fact that I would never go back there again. Many of my former classmates went to fight on the Russian side. I used to sit at the same desk with them, and then they were killing my friends who were fighting for Ukraine. A lot of my acquaintances from Cherkasy died in Popasna, a town right next to Holubivka, some 36 kilometers away. Two opposite worlds collided: my former life and the present one.

That was how I started life with the idea that I had no home and no place to go back to. So I had to move on. When my classmates went to their parents on weekends, I started going to Kyiv I fell in love with that city, and after a while, I moved there. I don't know how to explain it in words, but I feel very good in Kyiv, I love every street there and I just feel free and comfortable. Even when I walk off the bus and step on Kyiv's soil, I immediately get this feeling of emotional fulfillment.

In April, I relocated from Cherkasy to Chernivtsi on business. I work as a communication specialist at Media Development Foundation, an organization, supporting Ukrainian journalists. These two cities are very similar: cozy and friendly. However, I am trying not to get used to Chernivtsi, and am waiting for the time, when I will be able to return to Kyiv. I've been paying the rent for my Kyiv apartment the whole time. I think the entire office will be able to move to Kyiv in autumn. If it weren't for work, I would have been there long ago.

Over that time, I managed to make one trip home to Kyiv for a few days. It was in June, and it was the first time in four months. The city seemed very quiet to me as if it was trying to keep something a secret. Even the cars seemed to drive a little quieter. It certainly is not the same Kyiv I knew before the war. But I still love it very immensely

When I came to my building, I simply burst into tears... As I stepped into my apartment, I experienced very mixed emotions. I felt both at peace and thrilled to be back in a place I hadn't been to for a long time. Yet the next morning, I was so happy to wake up in my own bed.

For all this time, which is eight years, my parents have stayed in the occupied territories. I have already given up hope of persuading them to move; it is important for them to be home, and they are afraid of any drastic changes. They are adults who have made their choice, and it's not up to me to decide for them.

Naturally, it makes me sad, and I would like to be closer to my parents. At least to be able to have my family at one table for the holidays, as other people do. I haven't had that for years, and it's hard to imagine it happening, even though I often think about the future and dream about victory.

As a matter of fact, I can't imagine how to communicate with people who have lived for eight years in the occupied territories under the influence of propaganda. I just want us to drive a tank straight into our town, so that we could put on our vyshyvankas and say, "The time of your pseudo-republic is over, and we are finally bringing life back to this place." I mean a normal and civilized life.

Recorded by Olena Vysokolian

Translated by Volha Miknovich

Photographed by Ivan Pandikidis