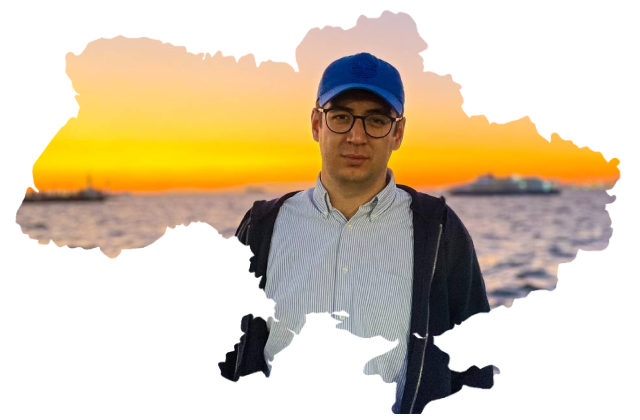

Bohdan Volynskyi

Architect, founder of the children's school of architecture "dash!"

Kharkiv — Repintsy — Ivano-Frankivsk — military service

I'd never spent more than a month away from Kharkiv before. My parents and grandparents were born here, and I feel a deep connection with this city.

On the night before February 24, I didn't sleep well. I had to wake up early for the express train to Kyiv, to get a health certificate for the Paris Half Marathon there. As I remember, it was supposed to take place in March. That was supposed to be my vacation trip.

With those thoughts in my mind, I woke up at five o'clock in the morning. I could hear a rumble, and I thought, "That's weird." It was clear that that was war, but I had no idea what to do. I spent some time in this state of stupor. Then I realized I was not going anywhere and had breakfast: I ate the sandwich I made for the road. That was an amazing sandwich.

At about 10 a.m., I went outside. I started looking for water and couldn't find it. An old lady I met in the street said: "There might still be water in that store." I headed there, and she followed me. Then it became clear that there wasn't enough water. I had two empty bottles, and so did she. I let her go forward, and she filled one bottle for herself and shared the other one with me. It was such a nice gesture, and I made everyone feel a sense of humanity and support.

wanted to join the Territorial Defence Forces, but they didn't take me. My mother lives in Saltivka and on the fourth or fifth day the electricity there was cut off, so she had to turn the phone off at night so it wouldn't go dead. At around that time my brother came to visit me. That day the rocket hit the neighbourhood where they stayed. I could feel that the danger was real.

I'd made the decision to leave Kharkiv by about the ninth day. One day I stood three hours in line in a supermarket and felt I no longer belonged there. I needed to get my mother, my girlfriend, Anya, (who is now my wife), and her little sister out of there.

The four of us got into the little car my dad lent me, a Suzuki Jimny. We didn't know where to go. We just drove forward. We drove in two cars, with my father and his family in the second one. He is an experienced driver, while I got my license the previous summer and had only driven once without an instructor before that.

One day we got stuck in Uman because there was no fuel. Then we got stuck in a traffic jam and stood there for seven hours. At some point, we lost our way, drove into a field, and almost fell into a hole. And it was at night, in the middle of nowhere, with no internet, only telephone connection.

I got a flat tyre this morning, and har to learn how to change it. Finally, my dad taught me; he hadn't done that kind of parenting before. After that trip, I learned how to drive, how to change a wheel, and how to inflate a tyre. I sorted out those issues in my 30s!

As a result, the journey took three days. We came across some nice people, who welcomed and fed us. We tried to thank them and pay for their kindness. However, for example, in a remote village, people said that it was all from the heart, and therefore, they didn't want our money.

Anya had relatives who had accidentally found a place to stay in a village in the Khmelnytsky Oblast. They had met an old man who offered them a place to stay in his house. We went there too, as two more rooms were available. So for some time, we lived in Repintsy, a village not far from Kamyanets-Podilskyi.

Later, I sent my mother to Austria and afterwards my girlfriend and her sister as well. Figuring out what to do next, I went to Ivano-Frankivsk. My friends there, the MetaLab organisation, are architects too. At the time, they were involved in the Co-Khata project that renovated old housing for displaced people to stay.

The girls from MetaLab hosted me in their home. They gave their own homes to the displaced people and moved into one. That was how we lived for a month or so. Every day we woke up, had breakfast, drove to the construction site, and went to bed after dinner.

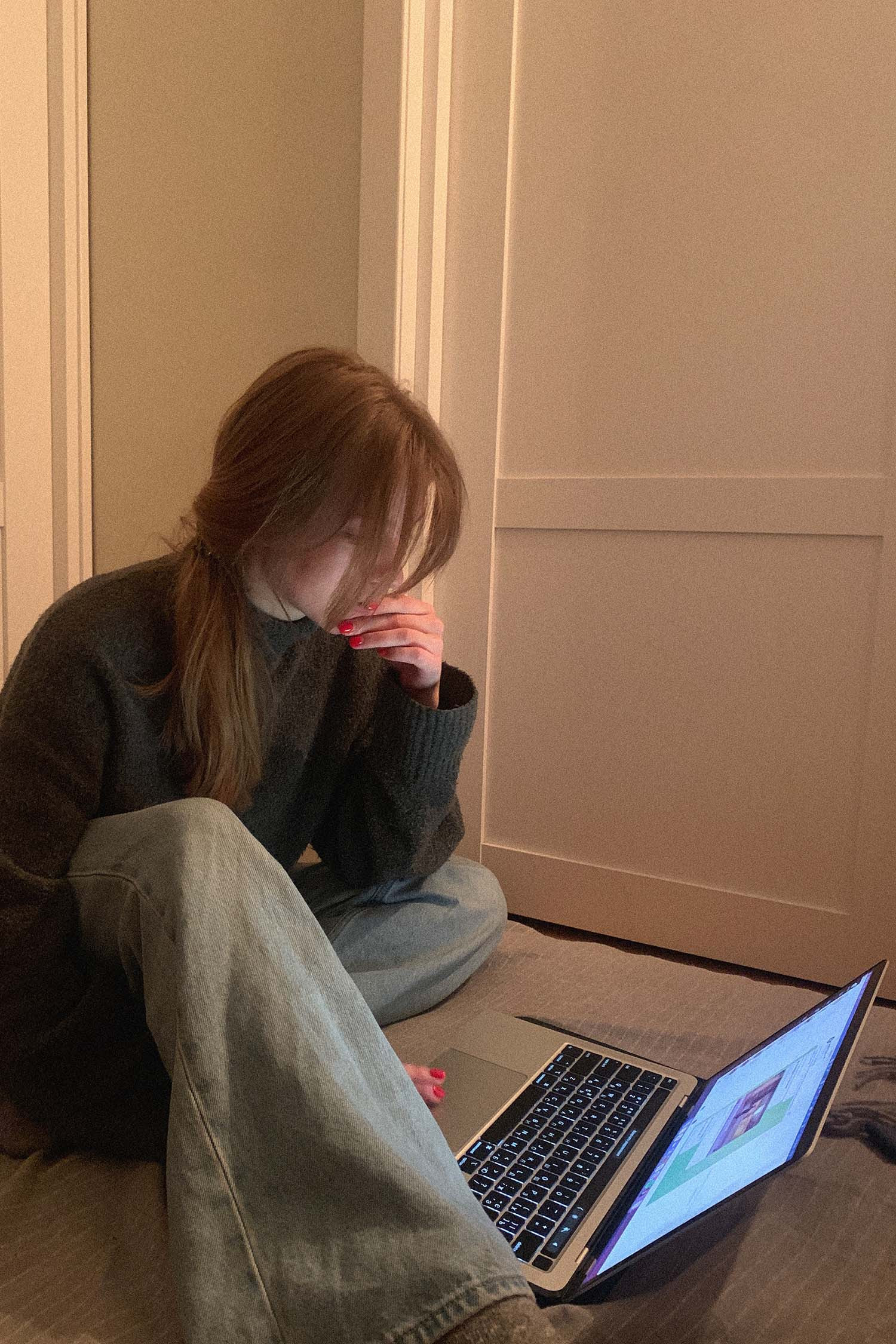

After a month, I discovered that a long-distance relationship is a challenging thing. My girlfriend took the initiative, came to Ivano-Frankivsk on her birthday, and decided to stay. We lived with an acquaintance of ours for a while longer, but then we decided to settle down together.

I continued to work on the "Co Khata" project. At the start, we worked with our own hands, but then volunteers joined us, so we had to organise them. That's how three months flew by in Ivano-Frankivsk. Of course, I felt deprived of home, even though I lived with friends who received me very warmly. The feeling of being homeless stays with you.

It was very difficult for me and my girlfriend to find a place to live. The offers were few and incredibly expensive. I didn't personally face any prejudice towards IDPs, but I heard complaints about people from the East, saying that they did nothing, just sat in cafes. I felt bad about people from Slobozhanshchyna because I identify with them. I think those were more of background talks given the fact that people didn't know where to vent their frustration.

Adapting to the new reality turned out to be a fascinating story. Girls from Kharkiv's Pakufuda café and Puchke bakery moved to Ivano-Frankivsk and started making their pastries there. I was looking forward to these buns, and when I saw them, the smell and taste brought back memories. I had tears in my eyes when I took a bite. I just couldn't eat them for a while.

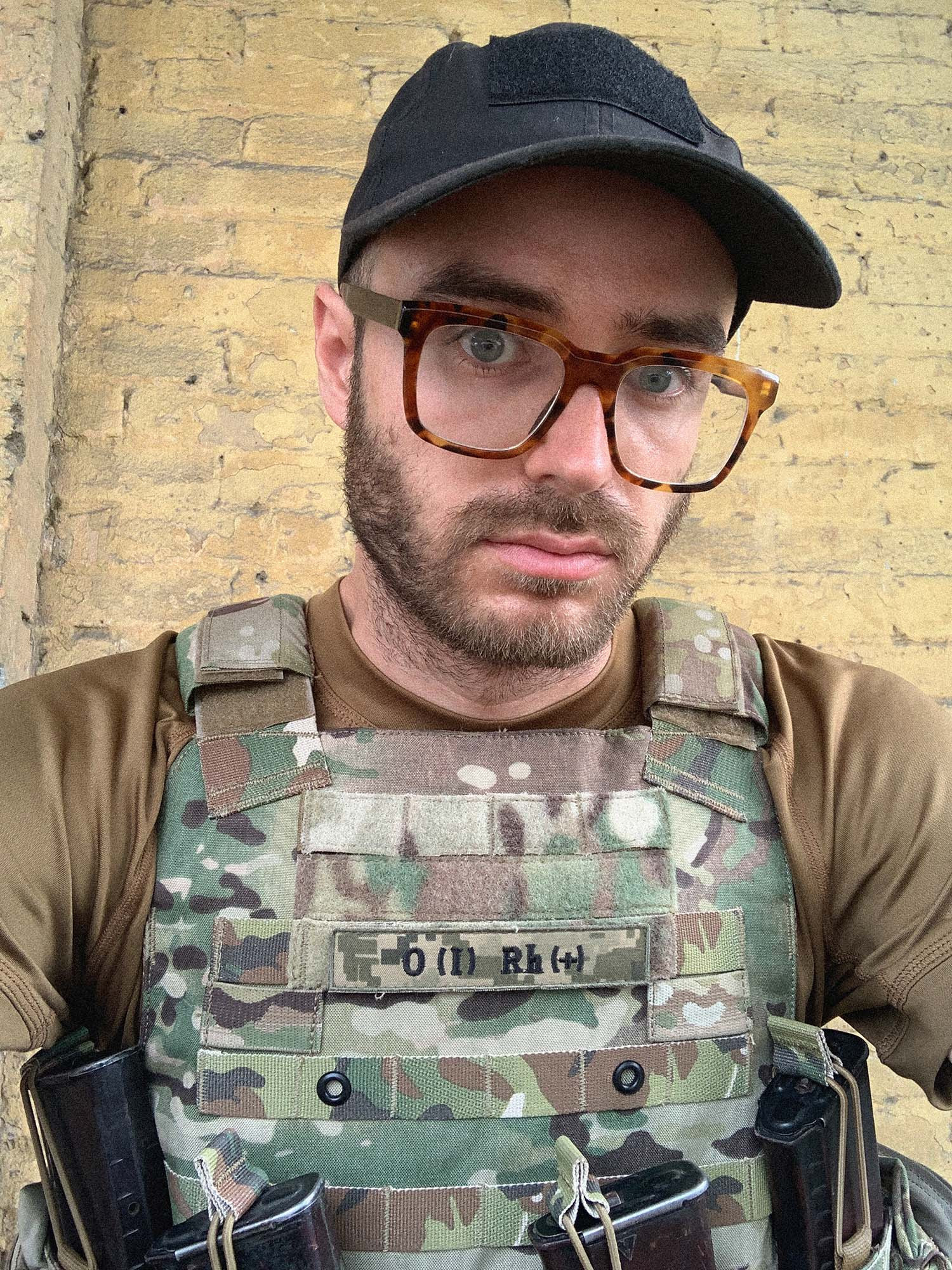

I didn't know many people who had decided to enlist. There were mostly talks about how to avoid the draft. I also had an automatic thought that I didn't owe anything to anyone and that it was better to help people where I was. But then it became clear to me that we would be engaged in humanitarian aid as long as the war lasted. In order to do something about this war at the moment, you had to go to the AFU and deal with the causes, not with the consequences.

It took me about a month to get to the military enlistment office because they sent me back and forth. When I passed everything, I asked if I was needed there. And I was told, "We need everyone who comes to serve consciously." So far I have met zero people who were forced to join the military. Some decided to join on their own, and some got invited, but I haven't heard of anyone being taken against their will. Everyone I have met here has voluntarily decided to defend the country.

When I still travelled from the military enlistment office to my unit, my apartment in Kharkiv got hit by a missile, and later the dash! studio got damaged. The windows were blown out and pieces of debris flew in. I don't know the full extent of the damage, but I hope that the library remains intact. Those two explosions in places directly related to me were also a very important thing. Not as important as the lives of the people taken away by this war, however. I mean this terrorism, this story in Olenivka. The crimes of the Russians are another reason why I decided to join the army.

While I was in Ivano-Frankivsk, the book I co-authored with Oleh Drozdov, Conversations on Architecture, was published by IST Publishing in Kharkiv. When we did the presentation in Lviv, I didn't feel super comfortable because it was the first major public event in a long time after the quarantine and the beginning of the full-scale invasion.

It made me feel weird that I was there presenting a book while people were fighting. I guess it made me start thinking.

I was also planning to release a book of poems, but it went to the publisher only when I had already joined the AFU. The title is Homework, and, in a way, it's about the work you do on yourself. One of the key thoughts in the book that I took for myself and wanted to share was that being an adult is about making decisions and then sticking to them. Joining the AFU for me is the proof of these views. It's about the ability to make a choice. And I made it for myself.

Another important decision I made during the full-scale war was getting married. My girlfriend Anya and I started dating shortly before the invasion. But after dealing with this critical situation, we realised that we were good together. At war a day counts for three, doesn't it?

When everyone you know is scattered all over the country or even the world, the whole country and the whole world become your home. Or it is nowhere if the places where you can meet someone you know are too far away. For me, home is people: relatives, loved ones, casual acquaintances. And being with my wife wherever we meet.

I used to think I was a citizen of the world, but a few years ago I realized that I really am very attached to Kharkiv. I recently released a poem dedicated to the city. It ends with the words: "It's not a place anymore, but an idea." Because Kharkiv is the people who fill it. They create Kharkiv, even if they're not there now.

Recorded by Sofiia Panasiuk

Translated by Volha Mikhnovich