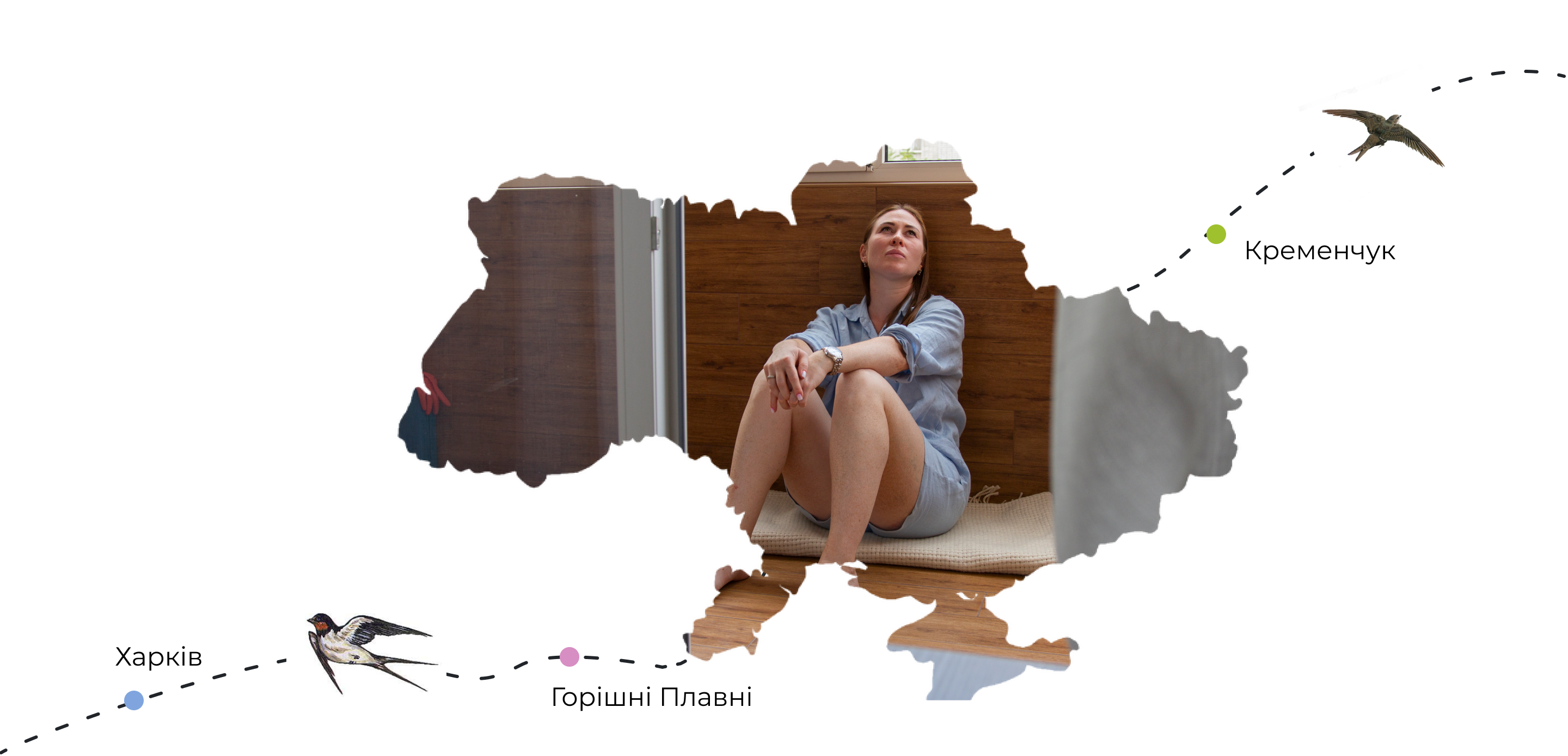

Luiza Ryzhkova

Marketing specialist, businesswoman

Kharkiv — Horishni Plavni — Kremenchuk

I am a native resident of Kharkiv: I was born here; I studied and made a career in this city. But Andrii, my husband, is from the Donetsk region. We first met in 2014, when he relocated from Donetsk to Kharkiv together with the company he worked for. Andrii was originally from the village of Novotroitske, which is very close to Volnovakha. Although this area remained Ukrainian after 2014, he and his family had endured a terrible experience that year. To be honest, I have only now realized what they had gone through.

My husband and I are peers: we both turned 33. Before the war for quite a time, we had been pursuing careers: I had been the head of the marketing departments of large retail chains, and my husband had worked in large companies as well. Moreover, two years before the war, we had started a family business. Thus, we had been constantly putting off having a baby. But I am grateful to God that we'd had time to bear and deliver a baby before the full-scale war. Now I have flashbacks all the time because last year I had the happiest pregnancy: I felt great and I was looking forward to the big event of my life. At the end of November, I gave birth to my son, and, in fact, we all lived incredibly happy lives until exactly February 24.

As for the time leading up to the war, I'll be honest, I was too focused on the newborn to care at all. My husband watched the news but tried not to disturb me. I only remember how on February 16 my best friend Dima wrote to me that there was going to be a war. I answered him very emotionally: "What are you talking about? What kind of war?" My reaction was no different from most people's: it was shock and denial.

And I clearly remember February 24. I woke up at 5 a.m. to explosions, and my husband's hastily dressing and saying, "I'm going to the petrol station". After surviving 2014, he knew that the first thing one runs out of was fuel. That morning Andrii managed to fill a full tank of petrol and as a result, we were able to leave in early March, because at that time there was no petrol in Kharkiv at all.

Our first decision was to leave, but when the news said that Russian tanks were coming from the side of Tsyrkuny, we decided to stay in Kharkiv to avoid the risk of getting into a potential trap outside the city. So on the first day, we went to the subway. We only sat there for a few hours, for we realized that it was not an option at all with a three-month-old baby.

Surprisingly, thanks to a friend of mine, I found a woman who had a basement close to our building. The space was equipped as a professional kitchen and it served as a real "bunker" for us, young parents with a baby and a labrador: it was safe, quite comfortable, with two exits and a large food supply

But already on the fifth day my husband and I started talking about leaving. The main reason was the electric power. We had a lot of food and filtered water, but I didn't have breast milk (it didn't come after delivery), so I couldn't breastfeed my son. The preparation of the formula required hot water and sterilization. We knew that as soon as a missile damaged the electric power line, we would be unable to feed our baby.

Another important reason for leaving was the car. In those days, missiles started to hit the Botanical Garden, which is 100 meters away from us. Andrii was worried that if the car got damaged, we would literally be held hostage by the city. We cherished that car as the pupil of the eye because, as my husband often said, it was "our ticket to another life". But the last straw was when on March 1 a bomb was dropped on Freedom Square. After that big bang in the city centre, I said confidently: "We are leaving today!".

It was decided that we would leave, but we were unsure of where to go. Going West was a no-go, because of the crazy traffic jams. Plus, the road there took so much time that it was simply impossible to make it there with a little baby. So we chose Horishni Plavni, a town near Kremenchuk. We deliberately avoided big cities to keep our child safe, because any big city means factories, bridges, and massive infrastructure. We were 100% certain that the enemy would aim there. And that was why we chose a small town.

What struck most painfully was the feeling of being a refugee. You had a home, a hometown, and a life with achievements and accomplishments. And now you are a nobody. You run around social services asking for help because you have nowhere to live. I mean, we ride with our newborn son, and we know there's a chance we'll be spending the night in a field. Because every room is taken. You call all these realtors, and there's nothing. And then they hear about the dog... This really hurt me as well: you're a refugee, nobody pays attention to you, and in addition to that you have a dog. My dog is my first child. There's a joke between me and Andrii that we have a skin baby and a fur baby because we love our dog like crazy. And when you hear "no dogs allowed", it kills.

But thanks to our son David, we were very lucky again. There was a family with an empty country house near Horishni Plavni that they were willing to give specifically to a family with a little baby. It was a small newly renovated house with a boiler, which is especially important for child care. The family was amazing; they helped us a lot by instantly organizing our life there. There was a thing that touched me the most. On the first day, when we moved in and were totally exhausted, our host brought us some homemade food: hot soup, buckwheat with butter, and some meat.

We lived in this place for three and a half months, all spring and part of June. But the feeling of being a refugee, of being cut off from home and of that hole in my heart didn't go anywhere. I mean, my baby was safe, my husband was by my side, my dog too, my car had survived, everything was fine. But there is no way you can forget that it is not your home and you can get evicted at any moment.

That is exactly what happened on May 22, when the landlady came to us saying: "Sorry, but we can't provide the house for the summer." So we started looking for an apartment and decided to move to Kremenchuk even though the oil refinery there got bombed regularly.

By the way, a rocket hit that mall in Kremenchuk two weeks after we moved in, not too far from our new home. But my husband, a logical and pragmatic person, chose Kremenchuk for a reason. He said: "This is central Ukraine, the Russian infantry will not get here because they need to get through too many cities to do so. As for missile attacks, Kremenchuk is a small town, it won't be shelled like Kharkiv or Kyiv."

I try not to complain about anything. I have friends who are now pregnant and are about to give birth — it is much harder than it was for me. I had a happy pregnancy, I give birth in normal conditions, not under bombing. We got the "bunker" and the comfy country house thanks to the baby.

But a child changes your way of thinking. I know I can't go back to Kharkiv, even though I love the city immensely, I can not imagine my life anywhere else after having lived the for 33 years. I can't go there because it's unacceptable to raise a child 30 km away from an aggressor who can start bombing at any moment. So we mentally prepared ourselves that we might stay in Kremenchuk for a year, or even two. Unfortunately, Kharkiv is a front-line city.

Recorded by Alyona Vorobiova

Translated by Volha Mikhnovich

Photographed by Vladislav Yevdokymov