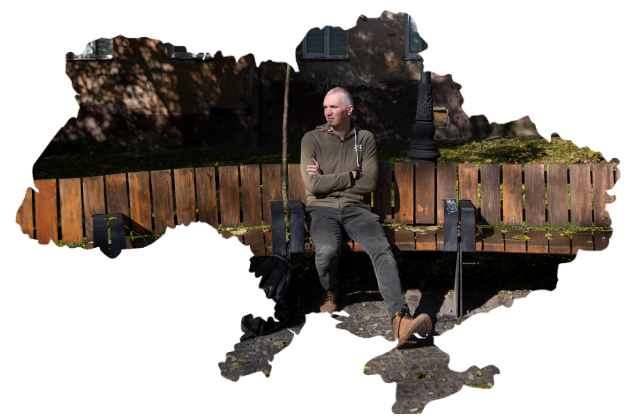

Kostiantyn Molchanov

Barista

Kharkiv — Ternopill — Romanove Selo (Ternopil region)

On February 24, at five in the morning my girlfriend woke me up with the words, "Dude, my dad called, the war has started, let's pack bug-out bags." I was still sleepy when I heard the first explosion and couldn't tell if I was dreaming or not. After the second explosion, I was fully awake.

We ran to the nearest metro station. There, some were on their way to work, others were hiding, some with their belongings, some with their pets. I have a lot of respect for the metro workers, it looked like they knew exactly what to do. They brought out the soviet water fountains, opened the toilets, and calmed people down.

I was born in Sievierodonetsk, but I was brought to Kharkiv at 11 months old. Many of my relatives stayed in Donbas. On February 24, the funniest and most surreal thing for me was when my grandmother from Donetsk called and said, "Kostya, I heard that you are in trouble there in Kharkiv, are you okay?" My grandmother from Donetsk told me that!

Later that day, we teamed up with some acquaintances, shopped, took the essentials, and got some canned food, because no one had any idea what was going to happen next. Later on, we started volunteering — we cooked food in the place where I worked. At that time we did not particularly feel the war. It felt like we were just having a good time, hanging out together, sleeping on tables. It also felt like I was a character in the Metro 2033 game because in that kitchen we only saw the sunlight when we were taking food out to the drivers. Going out every time felt like something heroic.

On March 6, I was walking by the thinnest wall and I heard a violent explosion as if it had struck our building. Everyone was frightened, and for the first time we went down into the basement. The next day my girlfriend told me we needed to leave. Evacuation from the Academy of Culture, where we studied, was to Ternopil. So we left for Ternopil.

When we got on the train, I felt nothing, but tiredness and a little anger. At that time there were already stories about evacuation missions being shot at, and at stops I pressed myself into the seat so that at least the metal hull of the train would protect me from the impact of the explosion.

On March 8, we got off at Ternopil and saw a huge line of people signing up as displaced persons right at the train station. The prospect of living in a gym with 50 people was not appealing. It turned out that my girlfriend's brother had acquaintances who lived in Ternopil, and they gave us the contact of a very nice man. This man, Volodymyr, straightaway invited us to his place, and gave us shelter and food. I spoke Russian then, but I decided that in Ternopil I had to speak Ukrainian. I began to mumble something, to top it all, we hadn't slept the night before, we had been driving for 17 hours. And he was like, "Just speak Russian, I understand everything.”

Volodymyr gave us towels, let us take a shower, and left us to sleep in his apartment, while he went to a friend's house. That is, he sheltered strangers in his apartment and, so as not to disturb them, he himself left.

The next morning we had breakfast and Volodymyr took us to Romanove Selo in the Ternopil region to have a look at a house where we could live. To be honest, I did not like that prospect very much, because at that time there were many checkpoints, no public transportation, no work, the house was not heated, and there were problems with water.

Over time, the house started to cosy up. The neighbours turned out to be very nice. Some absolutely incredible people work in the village council: they gave all the necessary advice, helped us, provided us with humanitarian aid, and gave us things and food. We were very lucky with the village.

It took us a while to adapt to life. The emotional state was a strange one. Work had kept us distracted from all the stress of the war, and we felt a lot of fatigue. And when we arrived and were able to exhale a bit, the stress came back like a spring. Everything that we experienced during the three weeks of volunteering came crashing down, and we could not do anything. Going to a store became incredibly difficult, and speaking to people — even more so. We would go out, buy some canned food, chips, and then lie on the bed and binge-watch soap operas or surf social networks. Sometimes we took a break for canned food and chips and then lay down again. It went on like that for about a month.

The fact that my girlfriend was around helped me get used to the new realities. Doing some routine chores like cleaning, bringing water, doing the laundry, and going into town also helped. As well as doing things I had done before the war. For example, going to a coffee shop, buying a pastry and coffee and sitting on the summer terrace kind of made me feel as if I had been home.

However, I still had the feeling that life had stopped on February 24, and that I was suddenly a ghost, watching what could have been happening. This whole story is a wound, and it's still fresh. And when I am recalling something, I am picking at it, roughly speaking. I realise that I'm living, but it's not a full life. I cannot detach myself and forget that there is a war going on, because how can I possibly forget?

When the war is over, I will return to Kharkiv. I don't know for how long. I want to walk down the familiar streets, and see my relatives if all of them are alive and well. To see my city, because I sincerely love it. To see with my own eyes my native places that were destroyed, to take pictures, to imprint them in my memory, so that my children and the next generation would not have a question about why we don't accept what is Russian.

What is Kharkiv to me? Its people. Although to a lesser extent now, because almost all my friends have gone elsewhere. And also Kharkiv is pleasant experiences. I don't remember myself not being in Kharkiv. And the fact that I`ve been living out of my city for half a year already was frustrating at first. And now I feel comfortable, so why cling to Kharkiv?

Before a full-scale war, I would say that Kharkiv was my home. But now I'm not so sure. Before, it seemed that to move somewhere or leave was just an ordeal. Now I see a lot of things differently, and if I have the option to go somewhere, and have money and time, then I just go.

I can't call the Ternopil region my home either, because I'm not a Halychian, this is not my place. Perhaps my home is where my parents live in Kharkiv, but I don't really want to go back to live with them even after the war. Perhaps my home is where my girlfriend is.

Recorded by Sofiia Panasiuk

Translated by Katsiaryna Khinevich

Photographed by Vladislav Yevdokymov