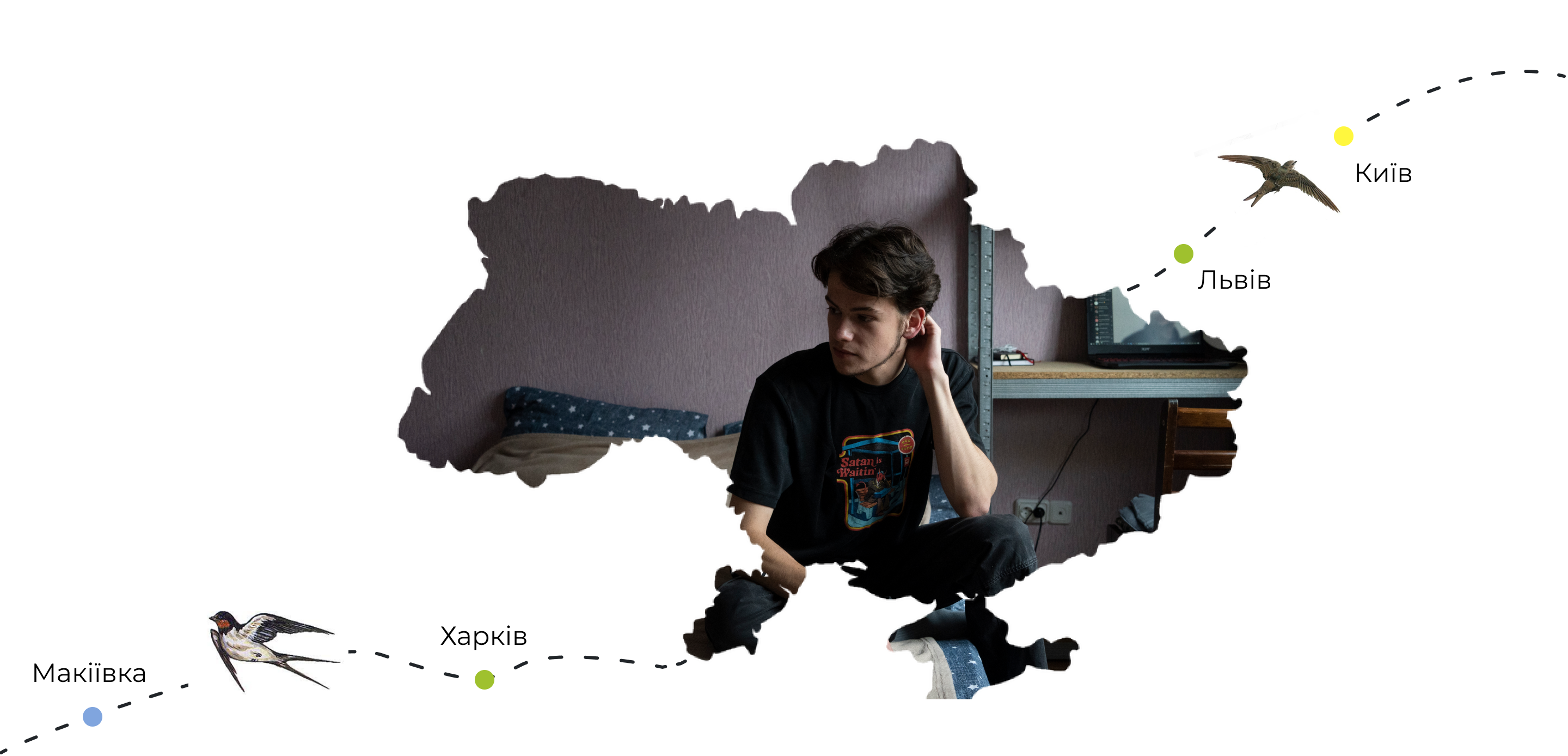

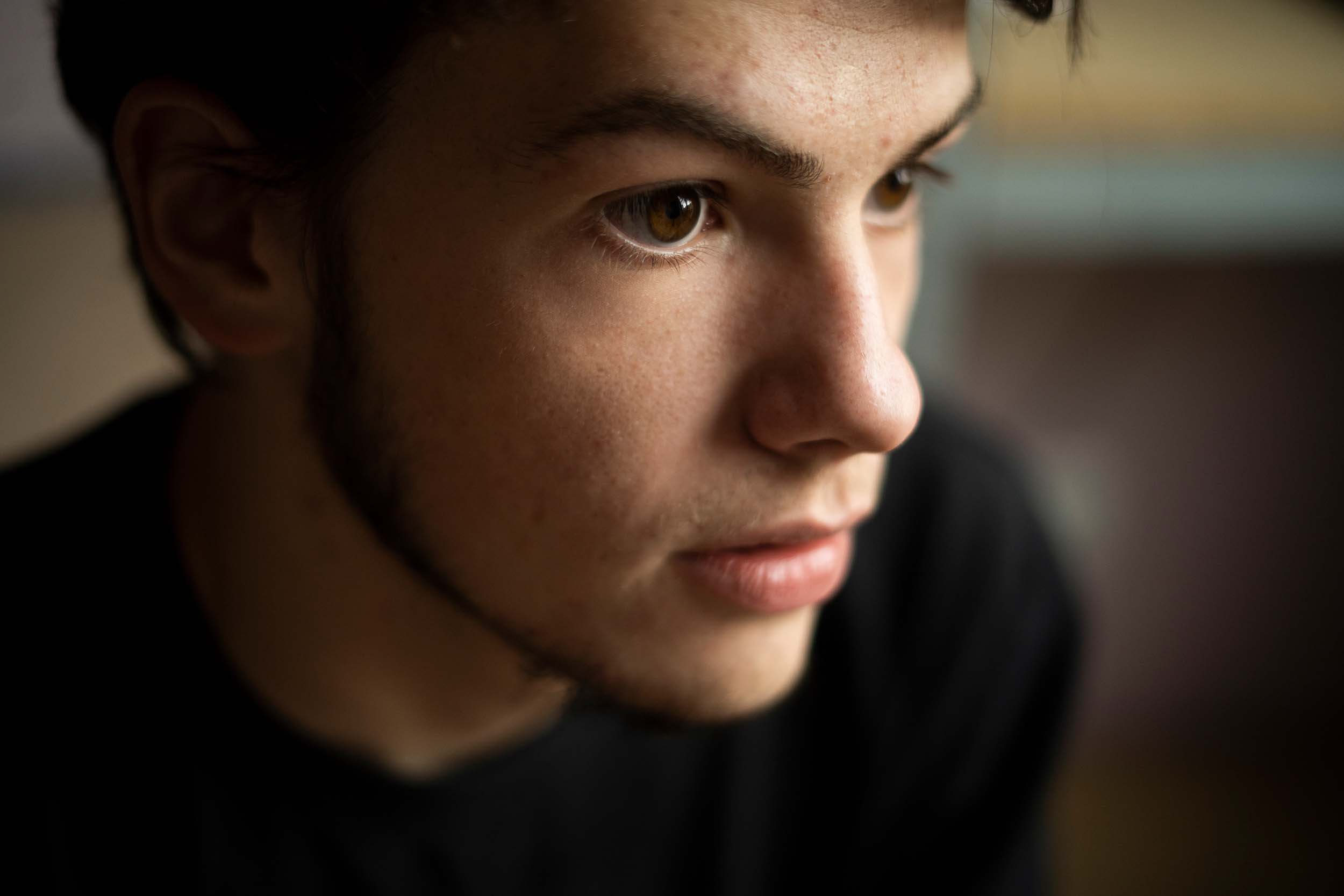

Ruslan Kravtsov

Student at Kharkiv State Academy of Design and Arts (KSADA)

Makiivka — Kharkiv — Lviv — Kyiv

I was born and grew up in the city of Makiivka, in the Donetsk region, which has been occupied for eight years. I left there when I was able to do it on my own. When I turned 18 I went to study in Kharkiv. Staying in the city where I was born was no longer an option.

I moved in February 2020, I didn't have a passport or a proper high school diploma. I didn't even speak Ukrainian: we hadn't been taught it in school since the sixth grade. Everyone close to me was against it: "Why should you study there, why not in our country or in the opposite direction?", that is, in Russia. But still, they helped me.

I got a passport and registered at a school in Volnovakha so that I could finish three grades as an external student and get my diploma. I spent the whole spring preparing for the ZNO*. The Ukrainian language was very interesting because in the first lesson I studied the alphabet. I studied with a teacher, who was almost the only one left in Makiivka able to teach.

When it was time to take my exams, my parents brought me to the checkpoint. The procedure was very long. In the first booth they checked my documents, in the second they made a sketch, took ten fingerprints, a panorama of my palms, and asked why, where and for how long I was going. Then there was the first search of the belongings, they checked my phone. It was hilarious because some old man with a machine gun took my phone and said, "Where are the buttons?" Then came some more questions: "Why are you going there to study? And when will you join our ranks?"

Then they inspect you one more time and put a stamp on the ticket. Then another search. After that, you go to a window and there a person calls somewhere and once again asks if you can be let out. Then there is the grey zone, zero checkpoints: first the DNR checkpoint, then the Ukrainian checkpoint. They check everyone there, too, but people have smiles on their faces. And it feels like home.

When I finally arrived in Kharkiv, the driver who drove me around the city asked where I came from because I was like an alien, I didn't know anything. I said that I was from Makiivka, and that was it — not a word during the whole trip. Only once the driver said: "Putin, of course, is a fucking asshole."

People have an interesting reaction to my passport as if I am always carrying a bomb with me. They start asking how long it has been since I moved, and why I have moved. And when they inspect things — for example, at the train station — they do it more thoroughly, looking for a second bottom in a bag. I'm not insulted, it's just a funny thing: for people, it seems like I already have some bad intentions straight away.

On February 24, I woke up in the dormitory and started collecting documents without even opening my eyes. My friend Liev from the city of Kramatorsk came in and immediately said, "Ruslan, it's started!" It was unclear whether this was really a war and whether it would continue or was a one-time incident.

One of my roommates woke up, and asked: "Are they bombing?" And the first thing he did at 5:30 in the morning was to call somewhere and say: "Hello, I want to sign up.” As it turned out later, he enlisted either in the Territory Defence or volunteered for the ZSU**. It was really impressive.

In the meantime, we all gathered in one room and talked about what to do. Everyone was calling relatives, I thought, "And I'll call mine too, tell them about my day." I called my grandmother, and she was like, "Don't worry, soon Kharkiv will be freed and everything will be fine." Who will it be freed from, me? I was shaking: how could my grandmother, whom I adore, say that at all? My mother reacted the same way.

In the dormitory, we decided it was better to go down to the basement. We went to the commandant to ask her if there was any way we could set it up. She looked at us as though we were crazy: "Has a war started?" That night we were all in the basement, her included.

Two days later, my boyfriend suggested that I come to Kholodna Gora, to wait it out at his place. It was very scary to go: I had the feeling that nothing was happening, but I would get in a taxi and something would fly right into me. Everything somehow happened in a second: I packed my things (the same things that I moved to Kharkiv with), ran to the taxi through huge snowdrifts, there were banging sounds somewhere. The driver drove very fast through the city because the roads were empty.

It was cosy in the basement in Kholodna Gora, and we stayed there for two weeks. Then the Lviv Academy of Arts offered to move KSADA students to Lviv for one semester and to provide housing. I decided that it was a good option for me because after two weeks in the basement I started to go a little crazy.

I have adjusted to life in Lviv, though it was hard at first. In the Academy dormitory in order to accommodate us, they had to ask some of their students to move out. Some went home, some went to Poland. They didn't care, but their parents couldn't understand why anyone else would live there if they had paid the money. But there was also a lot of help: people in the dormitory organized a kind of a second-hand and gave their stuff away. Some even made food for us. It was nice.

When we met the professors, I had an impression that we were treated with prejudice. Not that it was a bad attitude, but there were strange conclusions. For example, we were told, "And you probably don't even know Ukrainian.” Many people think, and I do too, that shouldn’t be a problem to adjust because we came out of the blue. At such moments, I feel incomprehension, I want to speak Russian in anger. But then you calm down, and everything is fine. My friends and I were recently in Uzhhorod, and somehow we only heard either very strong surzhyk or Russian. And during those two days, I missed hearing the Ukrainian language. It became very unpleasant to hear Russian from someone.

Now I feel comfortable, although at first, I had mixed feelings. I was thinking a lot about going back to Kharkiv. But I realized that I did not want to risk an arm, a leg, an eye or my mental state just out of curiosity, to find out how the city was. In general, moving was quite easy, because during a year and a half that I was living in the city I had not found anything that would hold me there. The whole temporary home I found moved with me to Lviv, so nothing has changed for me.

In August my boyfriend and I moved to Kyiv because we could no longer live in Lviv without paying for accommodation. There are more apartments for rent in the capital and they are cheaper now. Besides, I wanted to live in some more eastern city. Kyiv looks a little bit like Donetsk to me, probably because there are poplars everywhere. And I love that the Dnipro River runs here, the big water.

Before, when I lived in Kharkiv, I didn't miss Donechchyna. I wanted all my relatives to move out of there so that I could forget that it existed, it was just a black hole on the map. And now I feel that I really miss it a lot and want to be at home already, even though I have almost no one left there: only my father, with whom we do not communicate, and my grandmother, with whom we do not talk about war and politics.

For me, the state of the territories occupied since 2014 is intertwined with those occupied now — for example, in the Kharkiv region. If before I had the feeling that it was impossible to get it all back, now I see that the territories are being returned, and everything is possible. That is why I want Ukraine to be fully liberated and to go home with Ukrzaliznytsia***.

*ZNO — External independent evaluation or External independent testing is the examination for admission to universities in Ukraine.

**Armed Forces of Ukraine

***Ukrzaliznytsia — Ukrainian Railways is a state-owned company of rail transport in Ukraine

Recorded by Sofiia Panasiuk

Translated by Katsiaryna Khinevich

Photographed by Ekaterina Pereverzeva